This is a great psychedelic movies list that you must see.

Psychedelia in film is characterized by distortion (both in image and in sound), experimentation in narrative and editing, and sometimes drug-inspired hallucinations. Like the psychoactive drugs which produce heightened sensory perceptions and distortion, psychedelic films present to their audience an unfamiliar and/or dream-like view of reality.

The following films use cinematography, narration, editing, sound design, and music to create worlds of distortion. Whether the film is depicting drug-induced madness or creating an atomsphere of existential confusion, these films somehow experiment with the audience’s sensory perceptions in order to uproot the viewer from reality. These films welcome (or in some cases, force) the audience to interact with a plethora of psychedelic imagery, sounds, and/or narration.

1. Un Chien Andalou (1929) dir. Luis Buñuel

Even though Buñuel’s classic surrealist short film precurses psychedelia, the distorted narrative and dream-like imagery give it a psychedelic presence that influenced many films later on. His film is a perfect example of surrealism, a style of art which utilizes symbolism and the irrationality of the unconcious mind.

Un Chien Andalou was Buñuel’s first film, and was written in conjunction with Salvador Dalí, the prominent surrealist painter. The film opens with a barber slicing open a woman’s eye, as if to suggest to the viewer to symbolically throw off preconcieved notions and to see with new eyes.

The 20 minutes that follow are set to fragments of Wagner’s “Liebestod,” a dramatic piece of opera from Tristan und Isolde, that never quite comes to climax, making the film even more unnerving. Buñuel confuses his viewer by jumping back and forth in time with subtitles that proclaim “Eight years later” or “Sixteen years ago.”

There is no overt plot, but rather an amalgam of surrealistic images. We are presented with distorted religious symbology, such as ants crawling out from a stigmatic hand of the protagonist (a young unnamed man played by Pierre Batcheff), and dream-like scenarios- for instance, the young man dragging a piano topped with a dead donkey carcass and two priests in his pursuit of a young woman (Simone Mareuil).

Such images, surrealistic in nature, create a distorted sense of reality, a quality found in many psychedelic films.

2. The Red Shoes (1948) dir. Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s classic film The Red Shoes incorporates Expressionistic sets and costumes, subjective point of view shots, and passionate performances to tell the story of a young woman, dancer Victoria Page (Moira Shearer), torn between her love for a young man and her love of dance.

The dance sequence performed toward the end of the film captivates the viewer with its mesmerizing, painted landscapes and POV shots which sublty bring Victoria’s subconcious thoughts and fears to the forefront.

Victoria “Vicky” Page is a young talented ballet dancer, eager to join a company. She meets the fierce Boris Lermontov (Anton Walbrook), director of a renown ballet company. After realizing her talent in a small production of Swan Lake, Lermontov casts Vicky in his ballet of The Red Shoes, based on the Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale of a young woman whose red shoes possess her to dance to death.

Vicky then meets the young composer of the ballet, Julian Craster (Marius Goring) and the two fall in love, to the distress of Lermontov. Vicky is soon caught between the two men, forced to choose between the love of her life and her passion for her art.

Powell and Pressburger’s glorious Technicolor illuminates the passions of the film’s characters. The Oscar-winning sets provide an hallucinatory backdrop to the exceptional dance sequence, which brings Vicky’s fiery and tormented emotions to the limelight. The subtle POV shots during this sequence add to the psychological drama, and bring the viewer even further into Vicky’s mind.

A precursor of psychedelic filmmaking, The Red Shoes fuses hallucinatory elements into a mainstream film, which makes it a classic that continues to inspire modern filmmakers, such as Martin Scorsese and Brian de Palma.

3. Daisies (1966) dir. Věra Chytilová

Made during the Czech New Wave film movement by Czechoslovakia’s first female film director, Daisies is a revolutionary experimental film. Without following any real plot, the film is led by two impish young women as they whip up fun for themselves (and cause trouble in the process).

Věra Chytilová turns social mores on their head, as her two heroines, both named Marie (Jitka Cerhová and Ivana Karbanová) frolic through the film without a care. The two Maries laze around in bikinis and lingerie, create drunken mayhem at a nightclub, and destroy a fancy banquet, among other subversive acts.

The film explores different film stocks, spontaneous eruptions into collage, and otherwise consistently plays with the medium of film itself, creating a highly self aware piece of art. Banned upon release, the film depicts a destructive playfulness that Czech authorities apparently found dangerous. There is a political undertone to the film with World War II film stock intercut amongst the characters’ antics. Daisies stirs up the audience with its Puckish protagonists and psychedelic imagry and editing.

4. Point Blank (1967) dir. John Boorman

John Boorman’s neo-noir thriller, Point Blank is an hypnotic film of a man’s thirst for revenge. The pacing, color choices, and atmospheric music, led by Lee Marvin’s deadpan portrayal of Walker, yields a mesmerizing experience for the viewer.

Shot and left for dead on Alcatraz Island, Walker returns to San Francisco to take revenge and claim his half of a crime he helped commit. With the help of the mysterious Yost (Keenan Wynn), Walker sets off on his journey for retribution.

Along the way, he finds that the man who wronged him, Reese (John Vernon) not only stole his money and left him on Alcatraz, but he stole his wife Lynn (Sharon Acker), who is now a depressive, emotionless wreck living in guilt for double crossing Walker. After Lynn overdoses on sleeping pills, Walker finds Lynn’s sister Chris (Angie Dickinson) who helps him get closer to Reese.

The film’s pacing, which goes from a slow and moody atmosphere to periods of intense violence and action creates a lulling hypnosis which the viewer is then startled from. Color plays a role in the atmospheric tone of the film- for example, Lynn’s silver grey apartment reflects her drab unfeeling character, riddled with guilt.

Walker’s suits change color based on his location, giving him a mysterious chameleon-like quality. The story ends where it begins, on Alcatraz Island, leaving the film ambiguous as to whether the events that occur are a dream, reality, or if Walker is in fact a ghost.

5. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) dir. Stanley Kubrick

Stanley Kubrick’s science fiction masterpiece is an awe-inspiring, brilliant piece of art. The film’s stunning visuals combined with the grandeur of the classical music scores and György Ligeti’s haunting, dissonant avant garde music produces a filmic experience like no other. Kubrick’s exploration of the history and future of humankind excites the viewer’s senses as it leads us to confront the great unknown of space and time.

The film opens with the dawn of man as we witness the first protohumans utilizing tools for the first time in history. Through a graphic match cut, the prehuman tool becomes a spacecraft and we are transported to the future as humans have evolved and are now masters of their tools. The space craft is on a mission to investigate a mysterious object recently uncovered on a lunar crater.

A giant black monolith, also discovered on Earth by the protohumans earlier in the film, looms in this crater. We are to rediscover this black monolith again in the film. Next, we are on the Discovery One, a spaceship headed for Jupiter. Dr. David Bowman (Keir Dullea), Dr. Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood), and three other astronauts, in a state of cyrogenic slumber, are on a secret mission guided by the ship’s talking computer, HAL 9000 (voiced by Douglas Rain).

At this point, man loses control of his tools, as the computer’s intelligence superceeds that of the astronauts. Pitted against HAL, Bowman manages to take control of the ship and continues on the mission alone, traversing the wild unknown.

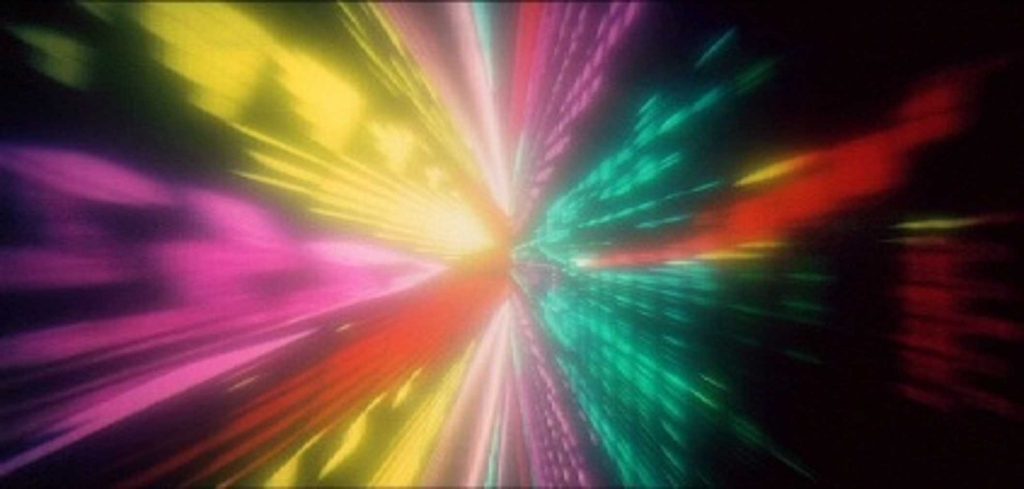

The film’s Beyond the Infinite sequence with its streaks of light in space and Ligeti’s dissonant chorus produce an intensely psychedelic experience. 2001’s enigmatic ending leaves the viewer spellbound and speechless. Kubrick exquisitely captures man’s existential journey into uncharted territory.

6. Easy Rider (1969) dir. Dennis Hopper

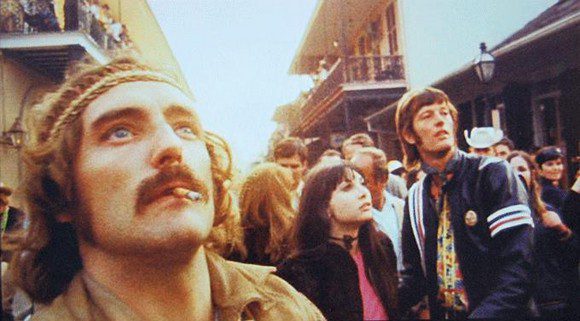

One of the America’s first counterculture films, Easy Rider captures the lifestyle of the hippie movement and how it interacts with the mainstream. Director Dennis Hopper and producer Peter Fonda also star in this pop culture hit as two hippie motorcyclists traveling through the American Southwest into the deep South. The film is not only historic in its depiction of the counterculture, but also in its realistic drug scenes (the actors actually injested the drugs their characters are shown using).

Wyatt (Peter Fonda) and Billy (Dennis Hopper) sell cocaine to a dealer and use their earnings to fund their roadtrip to New Orleans for the upcoming Mardi Gras celebration. Along the way, the two pick up a hitchhiker who lead them to a commune, filled with young hippies practicing free love and shared living.

Continuing on their journey, the two are arrested in a local town for “parading without a permit.” There, Wyatt and Billy meet George Hanson (Jack Nicholson), a drunkard lawyer in jail. George helps them out of jail and the three of them resume their pilgramage to Mardi Gras. The three are confronted with the ignorant, “square” communities in the South, who see the trio’s presence as a threat.

The film does an amazing job capturing the sociopolitical climate of the time. We see firsthand how feared the hippies were to mainstream culture, and how the counterculture was driven by a yearning for freedom. The scenes depicting drug use, especially the cemetary sequence in which Wyatt and Billy drop acid with two prostitutes, Karen (Karen Black) and Mary (Toni Basil), give the film an intense and disorienting component.

The unscripted LSD scene involves jump cuts, displaced, fear-filled and remorseful dialogue, and a mix of distorted imagery, such as the use of a fish-eye lense and close-ups of the sun. The psychedelic scenes mixed with the documentary style realism gives the film a palpable sense of the time.

7. Zabriskie Point (1970) dir. Michelangelo Antonioni

One part documentary-like realism, one part fanciful psychedelic desert trip, Antonioni’s American film offers its audience various aspects of life during the height of the counterculture. Although not critically well received, Antonioni’s cult classic remains a milestone of psychedelic filmmaking with its beautiful desert landscapes, hypnotic fantasy sequences, and a tailor made soundtrack from artists such as The Grateful Dead and Pink Floyd.

The plot is pieced around two young adults, Mark (Mark Frechette) and Daria (Daria Halprin), who meet in Death Valley. The film opens at a students’ protest meeting, where Mark is in attendance, with the overarching question of what makes a revolutionary. We follow Mark as he watches his friends in this group get tear-gassed, beaten, and one student shot by the police in a protest.

A police officer is shot and Mark is their suspect after he runs from the scene. He steals a small plane at a local airport and flies to the desert. Meanwhile, Daria is driving through a ghost town on her way to Pheonix to meet her corporate boss (and perhaps also her lover), Lee (Rod Taylor). Mark spots Daria’s car in the sky and flies down to meet her. The two cavort through the desert together before facing the dim realities that lie before them in civilization.

Antonioni’s film captures the recklessness of youth in this film that explores revolution and America’s counterculture. The dream-like scenes (including a sensual desert love scene that erupts into an orgy of sand covered bodies) transport this film from realism into earthy psychedelia.

8. The Devils (1971) dir. Ken Russell

Ken Russell’s controversial 1971 film incorporates sexually explicit hallucinatory sequences into this story based on the supposed demonic possessions in that took place in 17th Century Loudon, France.

An order of Ursuline nuns begin to exhibit wild, uncontrolled behavior thought to be led by Urbain Grandier (Oliver Reed), a proud priest, who has recently gained political control of Loudon. Sister Jeanne des Anges (Vanessa Redgrave), the sexually repressed hunchback Mother Superior of the convent becomes infatuated with Grandier, and her striking sexual fantasies haunt her guilty conscious.

Once word of Grandier’s secret marriage to another woman reaches Jeanne, she collapses into fits of hysteria and claims to have been possessed by the Devil through Grandier. Other nuns in the convent also claim to be possessed and the convent explodes into a frenzy of sexual outbursts and bizarre public exorcisms.

Russell boldly depicts the effects of sexual oppression mixed with religious mania. The censored scenes of the “demonic possessions” include a psychedelic orgy of naked nuns “raping” a statue of Christ and Sister Jeanne masturbating with a human bone. The uncut version of The Devils is a mind blowing, audacious exploration of ecstasy (both religious and sexual).

9. Wake in Fright (1971) dir. Ted Kotcheff

A relatively unnoticed 1971 Austrialian film, which was only recently restored in 2009 and released by Drafthouse Films, Wake in Fright is a nightmarish slice of life set in a barren small town in Australia. With its psychological, eerie tone (evoking an episode of The Twilight Zone), it puts the viewer in the mind of John Grant (Gary Bond), the film’s protagonist, as he slowly succumbs to his fate within “the Yabba.”

John Grant is a school teacher in the tiny town of Tiboonda in the Austrialian Outback, who is eager to travel to Sydney to meet his girlfriend over Christmas Break. With luggage in hand he gets on a bus to Bundanyabba (affectionately nicknamed “the Yabba” by its inhabitants), in order to fly to Syndey the next morning.

During his night there, John is immediately struck by an indefinable strangeness of the town. He is beckoned to join the drunken stupor that characterizes the town’s male population by the forceful friendliness of Jock Crawford (Chips Rafferty), a local policeman.

After a few drinks, John participates in the town’s favorite gambling game, to which he loses all his money, and his ticket out of the Austrialian Outback. Taken under the wing of Doc Tydon (Donald Pleasence), a self aware cynic and (the town’s only intellectual), John is driven to the point of desperation and the brink of insanity in his dusty prison.

The film’s moody tone as well as the superb characterization of life in an empty mining town puts the viewer in same psychological state of despair as John Grant. His intermittent daydreams, fantasies, and drunken hallucinations give us insight into his mind as we see and feel first-hand how his hopes are crushed by the stark desolation of the Yabba.

10. The Devil (Diabel) (1972) dir. Andrzej Żuławski

Żuławski takes his viewer to the roots of insanity through his passionate saga vividly illustrating the monstrosties of war. The sensational performances and dynamic camera work take the audience on an emotional rollercoaster through the depths of hell.

Amid the Prussian Invasion of Poland in 1793, a Polish nobleman named Jakub is imprisoned in a destroyed monestary turned hospital/jail/insane asylum. A mysterious, diabolical stranger on a white horse saves Jakub and the two of them, as well as a silent nun, embark to visit Jakub’s family and friends, whose lives are now crumbling. Jakub is driven to madness by the horrors around him, and with the stranger’s fiendish coaxing, Jakub commits brutal acts of violence (mirroring the all encompassing violence that surrounds him).

Originally banned in Poland upon release, Żuławski’s film delves into the shattered psyche of the inhabitants of war ravaged Poland. There are no understated emotions in Żuławski’s film; every character in the film goes through hysterical fits of rage, devastation, and/or lunacy. With the emotional extremes expressed by the characters, the disorienting camera work (that includes POV shots and handheld roving shots), and the wild, lo-fi musical score, The Devil presents its viewer with the chaotic sensory experience of a living nightmare.

11. Behind the Green Door (1972) dir. Artie Mitchell and Jim Mitchell

This feature-length pornographic film, released during the Golden Age of American porn, is as psychedelic as it is sexy.

A young woman (Marilyn Chambers) is kidnapped and taken to a mysterious location where she is hypnotised and led on stage in front of an audience. In a state of hypnosis, she takes part in a series of erotic performances.

During the sexual activites, the music slows into a ritualistic drone while the images saturate in color and overlap, lulling the audience into a trace-like state. Through the use of color saturation, music, and slow motion, the Mitchell Brothers mimick the state of hypnosis, creating a kinky psychedelic experience.

12. The Holy Mountain (1973) dir. Alejandro Jodorowsky

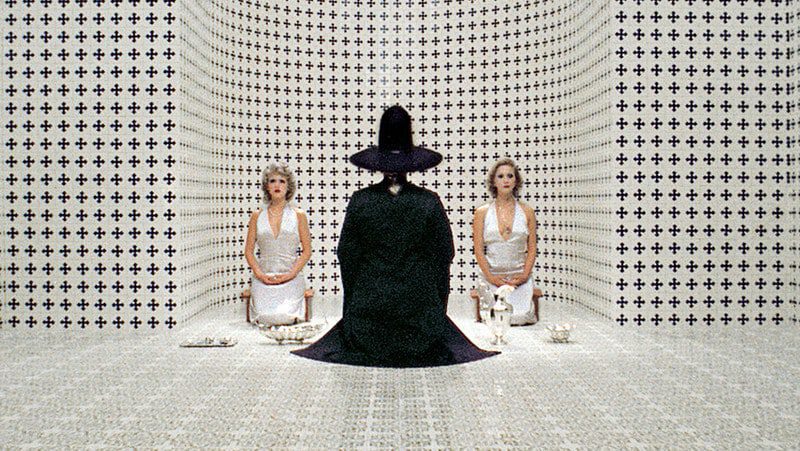

No psychedelic film list would be complete without a Jodorowsky film. The Holy Mountain, a surreal masterpiece abundant with religious symbology and references to Christianity, Tarot, and Alchemy, takes the viewer on a mind-bending spiritual journey. Like Buñuel’s Un Chien Andalou, the film opens with a symbolic and ritualistic action.

A cloacked figure takes two women dressed like Marilyn Monroe and sheds them of their societal regalia, removing their make-up, stripping them naked, and shaving their heads. Similar to Buñuel’s slicing of the eye, Jodorowsky is making a symbolic statement to the audience, to shed themselves of their societal standards and cultrually biased values. He then presents to the viewer a film that follows one man, known as the Thief (Horacio Salinas), and his mystical odyssey.

A Christ-like figure, the Thief, is found laying in pile of mud and garbage by a little person without hands or feet. The two go into town, where the people are performing a kind of religious ceremony, carrying crucified dogs while simutaneously executing groups of people, to the entertainment of tourists.

After the people of the town make a wax cast of his body for their mass-produced sculptures resembling Christ, the Thief journeys up a mysterious red tower and meets an Alchemist (Alejandro Jodorowsky), who leads the Thief on a path of enlightenment.

Jodorowsky has a way of creating original religious iconography. His film uses entracing music, symbolic characters, and surreal visuals in order to dissociate the viewer from common religious beliefs and typical cultural values. Jodorowsky immerses the viewer in his own world, an amalgam of mystical philosophies.

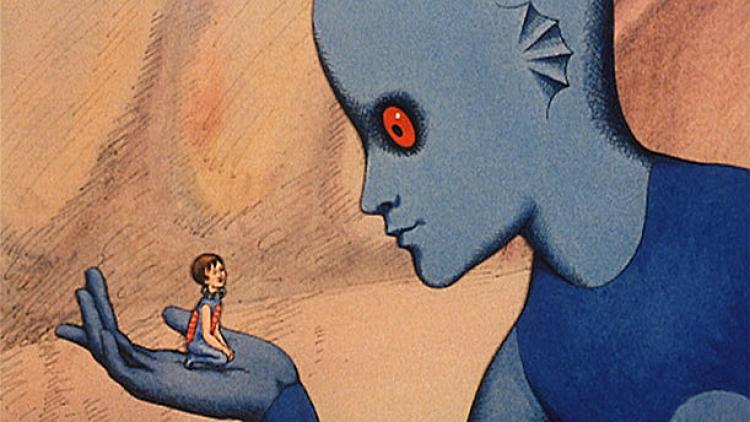

13. Fantastic Planet (La Planète sauvage) (1973) dir. René Laloux

This French/Czechoslovakian animated film introduces a strange, alien world in which tiny humans are governed by large humanoid creatures within a desert landscape brimming with monstrous exotic animals. This psychedelic science fiction adventure enmeshes the viewer into its bizarre microcosm.

In this realm, humans, known as Oms, live in tribes in the wild, while the large blue humanoid creatures with unblinking red eyes, known as Traags, control the planet. One day, a few young Traags are playing with an Om and her infant child. Things get a little rough and the Om is killed, leaving her orphan son.

A young Traag named Tiwa is passing by with her father and asks to take the baby Om home as a pet, to which her father agrees. Tiwa raises her pet Om, naming him Terr, and begins to form a strong bond with him. As Tiwa recieves her daily lessons through a portable headset, Terr listens and discovers the history behind Oms and Traags. He escapes with the headset, joins a group of Oms, and educates them, leading to an Om uprising.

Laloux’s imaginative story serves as a socio-political allegory, perhaps alluding to the Soviet forces controlling Eastern European states at the time. Regardless, the creative cut-out stop motion animation, with its foreign landscape, freakish creatures, and occasional hallucinagenic movement creates an eccentric head trip of a film.

14. The Wicker Man (1973) dir. Robin Hardy

This 1973 British cult film is experimental at its core as it plays with genre expectations, which baffle its viewer, and create an unusual filmic experience. One part investigative suspense, one part musical, and one part psychological horror, The Wicker Man infuses ancient pagan practices into the story of a police officer uncovering the mystery of a lost Scottish girl.

A young girl named Rowan Morrison is reported missing on a Scottish island called Summerisle and Sergant Howie (Edward Woodward) goes to investigate. Once on the island, Howie, who is a pious Christian saving himself for his wedding night, is shocked by the sacreligious pagan beliefs carried on by the people of the island. They are sexually free and seem to communicate mainly through song. Undetered, Howie attempts to get to the bottom of the Rowan Morrison disapperance, but instead finds himself delving deeper into Summerisle’s traditions of Druidism.

Robin Hardy has no problem experimenting with style in storytelling and genre. The folk music in the film acts as a storytelling device, mainly by issuing information subconciously to the protagonist (and the audience) as to the pagan belief systems that exsist on the island.

The Wicker Man’s soundtrack is well known to folk music fans, and may have influenced later psychedelic folk (a song from the film is included on a Psychedelic Folk compliation A Monstrous Psychedelic Bubble Exploding in Your Mind: Volume 1). Genre in the film is not clear cut, as it experiments with multiple tools from various genres. The aforementioned musical aspects mixed with the unsettling suspense and dark religious undertones yields a compelling and unique movie experience.

15. 3 Women (1977) dir. Robert Altman

Robert Altman’s enigmatic film captures the subtle strangeness of his characters within a destitute desert landscape. The psychedelic aspect of the film comes out in its ethereal tone, which, from start to finish, remains somewhat unsettling. The eerie music combined with the dreamy performances result in an otherworldly feel that sticks with the audience even after the film has ended.

The film begins at a health spa for the elderly and disabled, where Pinkie Rose (Sissy Spacek) is starting work. She meets Millie Lammoreaux (Shelley Duvall), and answers Millie’s ad for a roommate. Somewhat spaced-out, Pinkie struggles to appease Millie, who herself struggles for the attention and popularity she feels she deserves.

The two of them regular a local bar/shooting range where the bar owner, Edgar (Robert Fortier), and his wife Willie (Janice Rule) live. The very pregnant Willie quietly paints ominous murals while Millie vies for the attention of the drunken Edgar. After a failed suicide attempt on the part of Pinkie, the dynamics (and identities) of the women begin to shift.

The film reportedly was inspired by a dream Robert Altman had, which he adapted into a screenplay, and filmed, with the complete financial support of 20th Century Fox due to the director’s reputation. Altman achieves his dream-like state in this film, with its illusive characters, moody music, and exquisite direction.

16. Suspiria (1977) dir. Dario Argento

With its expressionistic production design and creepy soundtrack from Italian prog rock band Goblin, Argento’s cult classic is as trippy as it is eerie.

A young American ballet dancer, Suzy (Jessica Harper), moves to Germany to join a reknown ballet academy. However, upon arrival she realizes something at this school is awry: when she rings the front buzzer for entry, a mysterious woman doesn’t let her in, and that night two women are brutally murdered. After a weird encounter with one of the academy’s servants, Suzy faints. Things only get weirder during the course of the film with a variety of strange occurances and more mysterious deaths.

The film’s striking colors (especially the vivid reds), Art Nouveau-inspired architecture, and chilling musical score create a stylish and frightful hallucination.

17. Nosferatu: Phantom of the Night (1979) dir. Werner Herzog

Werner Herzog’s remake of the classic vampire tale takes the time-honored story to another level with his darkly poetic and hypnotic film. Herzog’s Dracula, played by the fascinating Klaus Kinski, is characterized as more of shriveled old man yearning for love than a fierce blood-thirsty monster. This interpretation of the character gives the film a poetic depth, which along with the trance-like music of Popul Vuh and gorgeous dreamy landscapes makes the film an entracing, meloncholic fantasy.

Jonathan Harker (Bruno Ganz), a real estate agent from Wismar, Germany travels to Transylvannia to meet Count Dracula and finalize the documents for the Count’s purchase of an estate in Wismar. On his travels, he is warned by local townfolk not to venture any further because of rumors that the Count is a vampire. Jonathan brushes them off as superstitious and continues on his journey.

Meanwhile Lucy (Isabelle Adjani), Jonathan’s newly married wife, suffers night terrors that seem to signify to her immanent doom. While doing business at Dracula’s estate, Jonathan’s locket with a picture of Lucy opens, and the ghostly Count becomes enchanted by her image.

Growing increasingly unsettled by the Count’s strange behavior, such as trying to lick the blood off a fresh cut, Jonathan investigates the Count’s castle and finds him asleep in a coffin. Jonathan escapes the castle, but the Count follows close behind, eager to arrive at his newly purchased estate and meet Lucy in person.

Kinski’s expressive moon-faced Count Dracula cross-cut with Adjani’s terrorized Lucy gives the viewer the impression that the two are metaphysically linked, even before they share the screen. This mystical bond the two share add to the dream-like aspects of the film.

The misty landscapes that permeate the film’s cinematography similarly place the viewer within this hypnotic countryside, set to the spellbinding score by the German avant garde band Popul Vuh. Nosferatu: Phantom of the Night is a mystic reverie that transports the viewer into that bewitching limbo between dreaming and wakefulness.

18. Altered States (1980) dir. Ken Russell

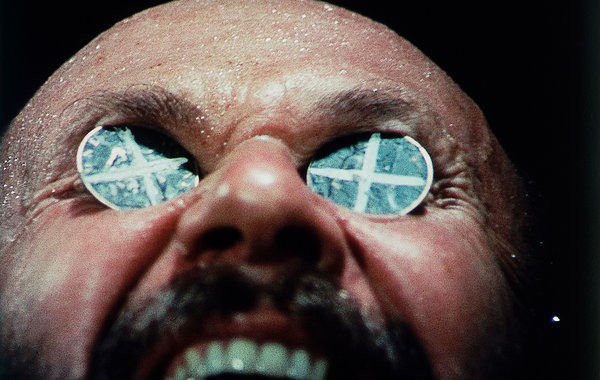

Ken Russell’s foray into the science fiction genre explores the mystical experience of one man’s hallucinations and the concept of these hallucinations becoming phyisically manifest. The film’s psychedelic sequences are vivid visual representations of the protagonist’s psychological devolution into increasingly primative forms of being.

A psychologist, Edward Jessup (William Hurt), fascinated with altered states of consciousness, undertakes a scientific experiment wherein he takes hallucinatory drugs while in a sensory deprivation tank. The combination of an untested Native American drug and sensory deprivation cause him to mentally and physically degenerate from man to proto-human to primordial being.

The sequences depicting Jessup’s hallucinations utilize bright colors and fast editing in order to show the viewer his altered sensory perceptions. We see religious and primal symbology, suggesting Jessup’s spiritual associations with his memories and unconcious thoughts. Toward the end of the film, his hallucinations become a wild daze of microscopic cellular movement.

Altered States is an excellent melding of science fiction and psychedelia in film. The surreal imagery adds insight into the consciousness of the main character while under the influence of his mind-altering experiences. There is a certain level of suspense during Jessup’s transformations, which make it hard for the viewer to determine what is real and what’s imagined.

19. Son of the White Mare (Fehérlófia) (1981) dir. Marcell Jankovics

This 1981 Hungarian animation uses bright colors, symbolic, geometric shapes, and pulsating movement to tell the mythic tale of a man with superhuman strength, Fehérlófia, born from a white horse. The film, abundant with allusions to ancient Hungarian history and folktales, visually captures the magic embedded in fairy tales.

We follow Fehérlófia through his heroic journey to exact revenge on the dragons that imprisoned his mother years prior. The film begins with his mother running for shelter and giving birth to him in the hollow of a tree.

She tells her young son the story of how evil dragons overcame the magic kingdom and imprisoned her. After having two sons, who disappeared from the eyes of the dragons, she escaped, pregnant with Fehérlófia. As he grows older, Fehérlófia receives advice from the spirit of the Forefather to suckle at his mother’s breast for 14 years in order to become strong.

At the end of the 14 years, his mother dies of exhaustion and he leaves home with his newfound strength to find his long lost brothers. The three of them then journey to the underworld to find the dragons who jailed their mother.

The striking, prismatic visuals lead us through this adventure rich with folkloric archetypes and symbolism. Jankovics creates a magical world with this fantastic story told through the colorful, psychedelic animation. The entirity of this film is one swirling mass of sensory delight.

20. Come and See (Idi i smotri) (1985) dir. Elem Klimov

This twisted coming of age tale illustrates the horrors of war as seen and heard by a Belarussian boy during the Nazi occupation of the Soviet Union during the Second World War. The film’s haunting imagry and sound design appropriately places the viewer in the vulnerable position of the impressionable young man as he sees his village viciously destroyed.

Flyora (Aleksei Kravchenko) is digging in the sand, looking for a rifle in order to join the Soviet forces. Once he finds his weapon, the wide-eyed youngster marches off to become a soldier, much to the dismay of his mother. On his troop’s first mission, Flyora is left behind with a beautiful young woman, Glasha (Olga Mironova), the troop’s nurse. German warplanes circle overhead and drop bombs on their camp site, deafening Flyora.

The film follows Flyora as he journeys back to his village, only to find it ravaged and occupied with sadistic Nazis. Once Flyora loses much of his hearing, the film takes a drastic turn, using warped sounds to mimic the sounds Flyora can hear. The drone of the airplanes overhead, the muffled voices of the people around him, and imagined radio broadcasts create the symphony of sound that permeate Flyora’s broken psyche.

At the start of the film we are presented with a bright eyed, bushy tailed boy ready for the adventures of war. However, we are only to see him traumatized and prematurely aged; he is driven mad by the terrors of death. The sound design mixed with the powerful performances (which oftentimes break the fourth wall) create a living nightmare that enmeshes the audience within the tortured mind of Flyora.

21. Dead Man (1995) dir. Jim Jarmusch

Jim Jarmusch’s atmospheric, existential western takes the viewer on the lonely, dreamy journey (accompanied by the sparse, electric strummings of Niel Young) of William Blake (Johnny Depp) as he finds himself wandering through a forest, led by a Native American named Nobody (Gary Farmer).

William Blake comes to the rusty industrial town of Machine with the prospects of a job. After his job falls through, he kills a man out of self-defense, and wounded, steals a horse and rides out of town. Nobody finds him unconcious in the woods and after learning William Blake’s name, thinks he is a reincarnation of the Romantic poet. William Blake takes a spiritual journey with Nobody through the white winter forest, realizing his place as a “dead man.”

Jarmusch himself dubbed the film a “Psychedelic Western,” and Dead Man lives up to the name through the use of Robby Müller’s exquisite, otherworldly black and white photography, Niel Young’s intense, yet minimal, music, and the philosophic musings of the characters.

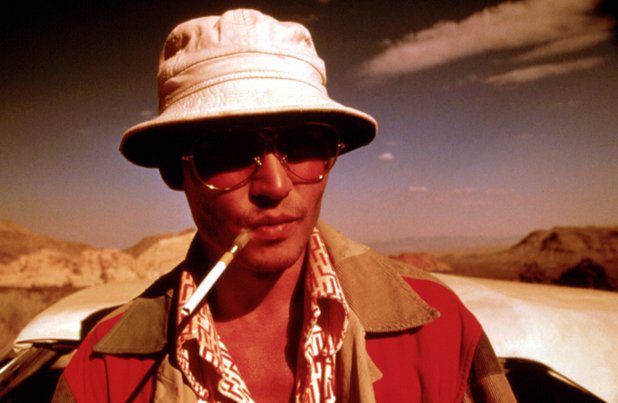

22. Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998) dir. Terry Gilliam

Based on Hunter S. Thompson’s novel (using semi-autobiographical events), Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas takes the viewer on a two hour psychedelic trip to the heart of debauchery. Consisting mostly of distorted caricatures and hallucinations, the film successfully envelops the viewer in the drug-fuelled reality of the characters.

Hunter S. Thompson’s alter-ego Raoul Duke (Johhny Depp) and his attorney, Dr. Gonzo (Benicio del Toro) take a road trip to Las Vegas from Los Angeles on the assignment of covering the Mint 400 motorcycle race. The pair feast upon their collection of illegal drugs, making their stay in Vegas memorable (well, from what they can remember). Duke narrates their indulgent exploration, bringing up themes of the American Dream.

In what could be considered the director’s cult masterpiece, Gilliam distorts the reality of the characters to the point of ridicule. As Duke and Gonzo cavort through the extravagant city of Las Vegas, with a multitude of drugs turning an already bizarre environment chaotic, they hit upon the emptiness of American culture.

23. Requiem for a Dream (2000) dir. Darren Aronofsky

Aronofsky’s melodramatic tragedy is a brutal tour de force. Depicting the mountainous highs and devastating lows of drug use and addiction, Requiem for a Dream goes far beyond any other cautionary tale with its horrifyingly distorted visuals, heartbreaking scenarios, and epic musical score.

The film follows four characters, Harry (Jared Leto), his mother Sara (Ellen Burstyn), Harry’s girlfriend Marion (Jennifer Connelly), and Harry’s best friend and drug dealing partner Tyrone (Marlon Wayans). Each character struggles to accomplish his or her ambitions, but is ultimately overtaken by their drug addition: Harry, Marion, and Tyrone to heroin and Sara to amphetamines in disguise as diet pills.

Aronofsky amplifies the drug use with continual close up shots of the characters injecting or ingesting their drug of choice. We see the routine that begins to develop and how it leads to the characters’ ultimate downfall. Visual and auditory hallucinations abound as the characters all try to maintain a grasp on their goals and in some instances, reality. Each characters’ descent is illustrated beautifully with Aronofsky’s masterful direction, with his emphasis on the distortion of reality that comes with drug use.

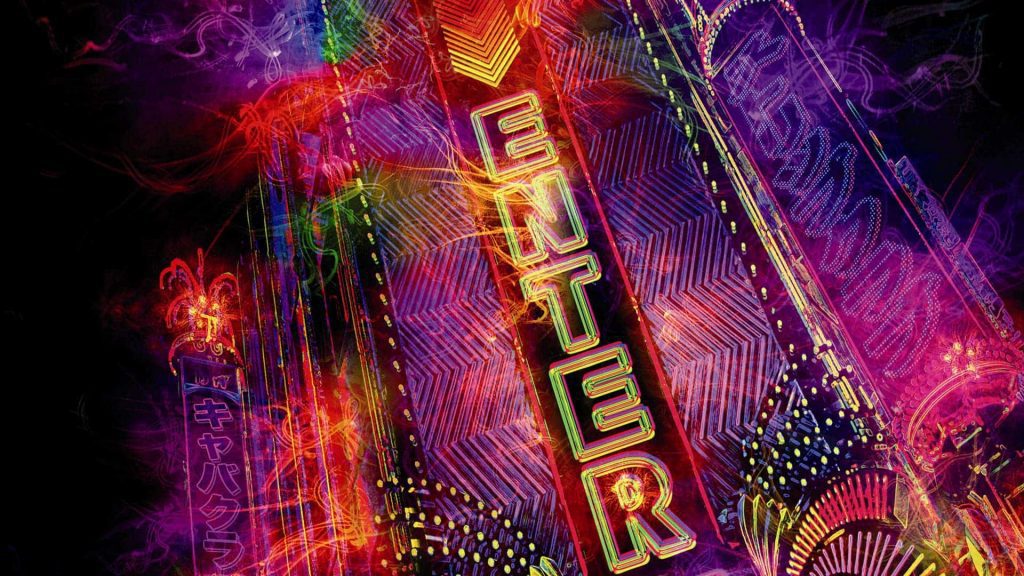

24. Enter the Void (2009) dir. Gaspar Noé

Gaspar Noé’s frightening, hallucinatory masterpiece is a sensory overload of bright lights and neon colors, a swirling soundscape, and unparalled visual effects. Noé’s hardcore mind trip transports the viewer into a phantasmagoric world of life, death, and nightmare.

Loosely based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead, the film follows Oscar (Nathaniel Brown), an American, Toyko-based drug dealer and his sister Linda (Paz de la Huerta). Oscar and Linda were orphaned at a young age, when their parents died in a car crash (that they were also in). The two promise to always stick together, and Oscar swears to protect Linda, no matter what.

One night, Oscar meets up with his friend Alex (Cyril Roy) on his way to a bar to sell some product to a young guy. The meeting turns out to be a set up, and Oscar is shot and killed by the police. For the rest of the film, Oscar’s spirit floats through the streets of Toyko reexperiencing old memories, watching over Linda and Alex, and delving into alternate versions of reality.

Told completely from Oscar’s point of view (the camera mimicks Oscar’s vision and hearing), the film captures every aspect of Oscar’s sensory perceptions, including a five minute DMT trip at the beginning of the film. The maelstrom of dazzling lights, neon colors, and distorted imagry that the viewer encounters both before and after Oscar’s death is nothing short of a tour de force in psychedelic filmmaking.

25. A Field in England (2013) dir. Ben Wheatley

A film made up of only five characters in one location, A Field in England takes the viewer on a psychological trip involving war deserters, witchcraft, and the supernatural.

Set during the English Civil War, an alchemist’s assistant, Whitehead (Reece Shearsmith) and three other deserters wander through the English Countryside in search of an ale house. The men come across a mysterious Irishman named O’Niell (Michael Smiley), whom Whitehead soon realizes is the man he was instructed by his master to find in order to obtain some stolen manuscripts. However, O’Niell pursuades the group of men to help him search and dig for a treasure buried in a specific field within a fairy ring, where the men soon unravel.

Ben Wheatley (Kill List, Sightseers) incorporates history and folklore into his very simple, yet compelling and extremely psychedelic film. The ancient superstition behind mushroom circles say that all those who enter are transported into a magical (but dangerous) realm.

Wheatley plays upon that superstition with psychedelic sequences that include mirroring one side of the frame to the other, and very fast editing which disrupts the viewer’s persistence of vision to the point of assault (there’s even a notice at the start of the film warning the viewer about the “flashing images and stroboscopic sequences”). The film achieves the perfect blend of historical realism and occult psychedelia.

Author Bio: Esther Zeilig is a graduate from UCLA’s School of Film and Television, with an emphasis in Cinematography. She spends her free time doing what she loves: watching film, working on her photography, and snuggling with her cats.