Since Swiss scientist Albert Hofmann accidentally discovered LSD’s psychedelic properties in 1943, a plethora of books, news articles, film documentaries, academic papers and conferences about the substance have seen the light of day. Add to that numerous artistic expressions – artworks, designs, films – that feature references to acid. It is simply fair to say that interest in LSD has been huge. However, most of the activity took place in (or is focusing on) the twentieth century. One may even get the impression that acid is a historical phenomenon that barely exists today. But nothing could be further from the truth. In fact, the past 15 years have seen many important developments in connection with LSD.

My first contact with LSD culture came primarily through the Scandinavian rave scene of the late 1990s. Had I been born in another time and place, my encounter with Hofmann’s potion – had it happened at all – would have been completely different. It should also be said that my perspective as a writer is that of a white male in his early forties living in Sweden, which of course has influenced my approach to writing the article. When discussing LSD culture, one should keep in mind that it is a global, multifaceted and loosely connected movement, and few, if any, psychedelic researchers can claim to know the full story of what has happened during the past decade and a half. Yet what follows is an attempt at outlining some of LSD’s recent underground as well as above ground use.

At the turn of the new millennium the future looked somewhat bleak for LSD. In his book Albion Dreaming, UK acid historian Andy Roberts says that during this time public interest in LSD was at an all time low, and that LSD appeared to be yesterday’s drug. Indeed, there was a major drop in availability of underground acid in the early twenty-first century, at least in the States. It is generally believed that the drop had to do with a particular event, namely the seizure of an LSD lab in Wamego, Kansas in 2000, which led to the draconian conviction of William Leonard Pickard and Clyde Apperson, now serving two life sentences and 30 years in prison, respectively.

The event has become known under several different names including the Wamego bust, the Pickard bust and the Kansas missile silo bust. The latter comes from the fact that the laboratory was stored in a renovated Atlas-E missile silo owned by Gordon Todd Skinner, a drug aficionado and con man moving in psychedelic circles. For reasons that are not entirely clear, Skinner decided to become a DEA informant and revealed the laboratory to the authorities. He received total immunity and was never charged for his involvement in the case. Incidentally, Skinner is now serving life plus 90 years for kidnapping-related charges. Titled “Operation White Rabbit” by the DEA, the Wamego bust is described by the agency as the largest LSD manufacturing case in history. Yet according to Erowid the scale of the laboratory’s production appears to have been vastly exaggerated. Many of the details surrounding the case nevertheless sound like something out of a crime novel.

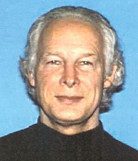

Leonard Pickard was an academic already in his mid fifties when he was arrested in 2000. In an SFGate article published that same year, he comes across as a somewhat unlikely figure to end up with two life-sentences for the large-scale manufacturing of LSD. Described by Mark Kleiman of UCLA as “a character out of a Pynchon novel”, Pickard is portrayed in the piece as a non-smoking and non-drinking vegetarian who runs marathons and practices yoga. According to Kleinman, Pickard is also a “superbrilliant chemist”. In the mid 1990s Pickard won a Harvard fellowship to study drug policy and addiction, and as the deputy director of the Drugs Policy Analysis Program at the UCLA in the late 1990s, he helped track the emergence of new street drugs in Russia. Although Pickard has a history of drug related arrests and convictions that go back to the mid 1970s, he has never made a confession in the Wamego LSD case.

Following his arrest in 2000, Pickard received backing by some seemingly unexpected characters, including the two “British aristocrats” Lord James and Lady Amanda Neidpath, the latter better known as Amanda Feilding of the Beckley Foundation. In a letter to the court the two vowed that Pickard was trustworthy. “We find it difficult to believe … he can be involved in anything criminal,” it said.

It seems most people, even within psychedelic culture itself, have accepted the Wamego bust as the main reason why there was an LSD shortage in the early 2000s. “The best explanation is a bust, a really big bust,” wrote Ryan Grim about the LSD drought in his article “Who’s Got the Acid” published in Slate magazine in 2004. There is, however, reason to be a little critical towards this popular, and not to mention media-friendly, explanation. Although it appears the Wamego bust was something of a blow to acid culture in the early twenty-first century, at least in the States, there are several additional factors that may have strongly contributed to the acid shortage.

In his piece “International LSD Prevalence: Factors Affecting Proliferation and Control”, written by Pickard by hand from prison and presented by writer and Mind States conference co-founder Jon Hanna at the World Psychedelic Forum in Basel in 2008, Pickard says that the drop in LSD availability partly had to do with the great influx at the time of MDMA, which he believes had a displacement effect on LSD use. According to Pickard, another major reason for the shortage of LSD in the early 2000s – which actually had been in steady decline since 1996 – had to do with difficulty in obtaining one of the key materials used by chemists when producing LSD, namely ergotamine tartrate (ET). Since the early 1990s, ET is subject to strict controls in most countries. “This synthetic bottleneck, the dependency on ET supply, may be the most important single factor affecting proliferation of clandestine laboratory sites,” wrote Pickard.

In 2000, Federal, State and local forensic laboratories in the U.S. analysed 1,785 exhibits of LSD. The following year the number was down to 1,368, and in 2002 a mere 198 samples were analysed. Although there is no arguing that this was a remarkable drop, most people discussing the U.S. LSD drought rarely mention the fact that availability of the drug actually increased throughout the decade. After having remained low for a couple of years, the number of LSD exhibits that were analysed slowly increased to 844 in 2007. While this number is relatively low compared with what was seen in 2000, it nevertheless shows that there was still an existing American LSD culture at the end of the decade.

According to the DEA, very few labs are responsible for the worldwide LSD production. In 2010, they stated that, “A limited number of chemists, probably less than a dozen, are believed to be manufacturing nearly all of the LSD available in the United States.” However, according to Pickard it is more likely there are many small labs operating that are less easily detected and easier to move. In his paper, Pickard mentions Casey William Hardison as an example of someone who was running one such small lab. The latter made LSD and other psychedelics in a lab that would to fit into a bedroom.

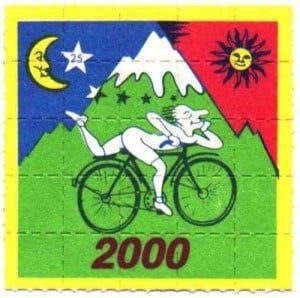

Despite the shortage in the early twenty-first century, there were certainly many people who continued to take LSD. For example, this was evident by the appearance of “Hofmann Millennium” around 2000, a reissue of a blotter LSD from the mid-1990s. The blotter features an illustration of a smiling Albert Hofmann taking his legendary LSD bicycle ride in the Swiss countryside, complete with a snow-clad mountain in the background. Already a classic, the image has become one of the most well-known examples of blotter art produced over the past decades, and, besides having appeared on t-shirts and other commercial products, un-dipped “vanity” blotter can be bought online. Clearly, there were enough acid enthusiasts out there to make sure LSD would survive into the new millennium.

In the early 2000s, LSD was also present in art. For example, in 2000 British visual artist and art world superstar Damien Hirst, believed to be one of the wealthiest living artists in the world, made an artwork titled Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD). The motif, which features a number of coloured dots, has been reproduced on several commercial products including an “LSD” iPhone case, making sure your phone is always on acid. Another artist taking interest in LSD in the early twenty-first century was Rodney Graham. In his 2001 film The Phonokinetoscope, Graham made a re-enactment of Albert Hofmann’s original 1943 LSD bicycle ride. Naturally, the artist himself was on acid while making the film. Although many of today’s psychedelic artists take inspiration from a wide range of mind-altering substances, including plant based psychedelics such as ayahuasca and psilocybin mushrooms, LSD continues to be used for artistic purposes in the twenty-first century. For example, visionary artist Luke Brown sees LSD as his probably most consistent influence, and several artists featured in the art book Juxtapoz Psychedelic (2013) list acid as a source of inspiration.

The early 2000s also saw the release of Connie Littlefield’s excellent documentary filmHofmann’s Potion (2002). Using the tagline “The story of ‘acid’ before it hit the streets”, it featured unique interview material with Hofmann and other senior key figures in psychedelia. And when it comes to literature on psychedelics, Marlene Dobkin de Rios turned to the subject of LSD in her 2003 book LSD, Spirituality, and the Creative Process, which was based on Dr Oscar Janiger’s LSD research in the 1950s and 1960s. Looking at acid and its accompanying culture from a broader perspective in the early 2000s, its influence was also still very much seen in psychedelic manifestations such as the, at the time, recently started Boom Festival in Portugal, and of course the Burning Man festival in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert.

Moving on to the mid 2000s, LSD again made the news when the aforementionedCasey William Hardison, an American living in Britain, was arrested in February 2004 for making psychedelics. Alongside DMT and 2C-B, Hardison manufactured LSD. Interestingly, just like Pickard many years earlier, Hardison was an active figure in the psychedelic subculture, and in addition to attending psychedelic conferences he wrote articles for MAPS and Erowid. Talkative and quick-witted, Hardison acted as his own lawyer during his trial. Being an advocate of cognitive liberty, he argued that it was his human right to use entheogens. His arguments were rejected, and after an eight-week trial Hardison was convicted in March 2005. As is usually the case when it comes to LSD, the sentence was stern: In April 2005 Hardison was sentenced to 20 years imprisonment in the United Kingdom.

Illicit drug manufacturers are generally seen as unscrupulous and greedy individuals with no morals by society at large. Yet it is safe to say that Hardison was an acid idealist with a strong belief in LSD’s transformative potential who became yet another victim of the War on (some) Drugs. In a recorded message played at the World Psychedelic Forum in Basel in March 2008, Hardison, at the time four years into his sentence, made sure to remind the audience that, “It is easy to forget that the majority of those present in this forum, who have tasted Albert’s Problem Child and Wonder Drug, LSD, probably did so via the flask of a chemist who was risking severe restrictions on his or her liberty simply to bring the blessed entity, LSD, into existence.”

During the years leading up to his release in May 2013, Hardison became something of a legend in his own time, at least to some people in the inner circle of contemporary psychedelia. A website titled Freecasey.org was launched, making sure his case was not forgotten, and after he was released he appeared on the Dose Nation podcast and was interviewed live via Skype by his wife, psychedelic researcher and cognitive liberty advocate Charlotte Walsh, during the 2013 Breaking Convention conference. Appropriately enough he was also back writing for Erowid.

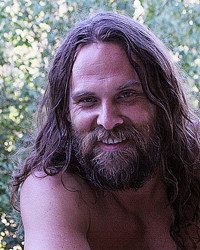

So what motivates an individual such as Casey Hardison to manufacture LSD? The answer might lie in the drug itself. It is my guess that the vast majority who make acid have had powerful transformative experiences themselves, and want to give others the opportunity to reach similar altered states of consciousness. Hardison, an alcoholic from the age of 14 who found his way to the 12 steps of the AA, first took LSD on a cold night in December of 1993. It was a solid dose of approximately 250 micrograms, and during the trip he experienced oneness of all things. “Perennial wisdom dawned and my heart burst forth in praise, gratitude and love, rooted in a mindset of compassion for self and other,”[13] he eloquently wrote in his piece “(A Brief History and) Motivation of an Entheogenic Chemist”. Needless to say, acid made a huge impact on Hardison. So much so that he made a commitment to himself that he would synthesise LSD.

In late 2003, ten years after his first acid trip, Hardison was given “a mass of dark resinous material purported to be ergotamine tartrate (ET)”.[14] ET, as you may recall, is the sought after material used by underground psychedelic chemists for the purpose of making LSD. In February 2004, after having failed repeatedly in his attempts, Hardison succeeded in making LSD from the ET he was given. “In ordinary circumstances, I might have been awarded a novel synthesis patent; instead, I was awarded a twenty-year prison sentence.”[15]

So far, this article has discussed LSD made by underground chemists, and for obvious reasons people who use street acid very rarely know the dosage and purity of the substance they are about to ingest. Occasionally, it is also discussed whether or not street acid actually contains any acid. However, when it comes to the mid 2000s it seems the vast majority of the substances that were sold as LSD blotter or microdots did in fact contain LSD. A 2005 analysis carried out by the Spanish Medicines and Health Care Products Regulatory Agency showed that LSD was indeed detected in all the samples that were tested. Eleven of the samples had their place of origin in Spain and an additional six originated from Switzerland. Interestingly, the quantity of LSD found on the samples was very low.

Two of the blotters, “Marilyn” and “Pink Triangle”, only contained 19 micrograms of LSD each, and the three microdots in the analysis each contained between 20 and 26 micrograms. Of the 17 samples, eight of them contained less than 30 micrograms. The sample with the largest quantity of LSD in the study contained 102 micrograms.[16] If the latter sounds like a large dose, one should keep in mind that a common dose in the sixties counterculture was about 250 micrograms. Many of the blotters and microdots in the Spanish analysis contained threshold doses, which only produce mild, sometimes barely noticeable, effects of the drug. The lowest doses that were found in the Spanish analysis were in fact equivalent to the ones used when microdosing LSD. It is also common that a single blotter LSD is cut in pieces and shared between users, which, if it is weak to begin with, makes the drug little more than a placebo.

Paradoxically, low doses of LSD can sometimes produce anxiety.[17] Generally speaking though, when people are taking acid recreationally in crowded settings such as nightclubs and festivals, where many other drugs such as MDMA, amphetamine, cannabis and alcohol are used as well, low doses most likely prevent many difficult experiences, and as the former LSD chemist Tim Scully pointed out in 2003, “One blessing of the small doses popular now is that extreme bad trips are more rare.”[18]

When it comes to the Spanish analysis, one also needs to consider the handling of the 17 samples. Needless to say, poor handling by street dealers/users or those who carried out the analysis may very well have affected its outcome. Once LSD is added to a sheet of blotter, it is extremely sensitive. According to Scully, blotter is a “very bad distribution method since it leaves the acid vulnerable to rapid decomposition”,[19] and his old colleague, the legendary LSD chemist Owsley Stanley, wrote in an email exchange with the present writer in 2003 that, “Blotter is not even stable for 30 hours. Deterioration commences as soon as the liquid carrier is soaked into the paper.”[20] Hence, many of the LSD blotter samples that were used in the Spanish analysis may in fact have been more potent when they were fresh from the lab. That said, it is still safe to say that LSD doses in the twenty-first century are generally considerably weaker than they were in the drug’s early days.

In the case of LSD and other psychedelics, the subject of dose is often overshadowed by set and setting. While the latter two are extremely important for the outcome of the psychedelic experience, dosage can make all the difference too. As has already been mentioned, the low doses that have been prevalent in underground LSD culture in the twenty-first century have most likely prevented many emergency room visits. Yet it has also resulted in a generation of threshold trippers who sometimes have a poor understanding of LSD’s transformative and therapeutic potential. Clearly, ingesting a threshold dose is very different from taking a medium to high dose, and in order to utilise LSD’s visionary and healing effects, it is questionable if these are obtainable in situations of low-dose use.

Like any other movement, LSD culture has its own pioneers and celebrities. The first 15 years of the twenty-first century have seen the passing of several of these characters including Merry Prankster Ken Kesey (d 2001), psychiatrist and LSD researcher Oscar Janiger (d 2001), psychiatrist Humphry Osmond (d 2004), author Laura Huxley (d 2007), underground acid chemist Owsley Stanley (d 2011), author and psychedelic researcher Myron J. Stolaroff (d 2013) and author and orator Stephen Gaskin (d 2014). In their own unique way, these people are forever part of the history of LSD. In addition to the ones just mentioned, the 2000s also saw the passing of one of psychedelia’s most celebrated characters, namely Dr Albert Hofmann. When the Swiss scientist died in April 2008 at the age of 102, his discovery had affected millions of people worldwide. Needless to say, LSD took on a life of its own early on, and during his lifetime Hofmann saw how the drug he discovered was adopted by scientists and academics, followed by various subcultures including the hippie counterculture, the Deadhead scene and parts of rave culture.

Besides a number of vibrant LSD subcultures, Hofmann lived to see how psychedelics, through the strenuous efforts of organisations such as MAPS, Beckley Foundation and Heffter Research Institute, were beginning to find its way back to science. So, even if LSD seemed like yesterday’s drug at the start of the new millennium, it was clear that by the mid 2000s, Hofmann’s potion still had quite a following. This was evident by the appearance of a 2006 conference in Basel celebrating the Swiss scientist. Titled “LSD: Problem Child and Wonder Drug: International Symposium on the Occasion of the 100th Birthday of Albert Hofmann”, the three-day conference attracted over 2000 visitors from 37 countries. More than 80 experts delivered talks on the subject of LSD, and besides Hofmann himself, the speaker list included most of the who’s who of contemporary psychedelia. If anything, the event was proof enough that LSD had survived into the twenty-first century.

As the years went by in the new millennium there were many signs of a growing interest in LSD. Several retrospective works discussing the drug appeared in the late 2000s, including the 2008 books Psychedelic Psychiatry by Erika Dyck and the aforementioned Albion Dreaming by Andy Roberts. The late 2000s also saw the release of the film documentaries Peyote to LSD (2008) and the National Geographic Explorer film Inside LSD (2009), the latter narrated by actor and former Digger Peter Coyote. LSD also made a cameo in Gaspar Noé’s DMT inspired 2009 film Enter the Void, which features wise words or platitudes, depending on what you make of it, such as the following line from character Alex: “You know the good thing about LSD, if you can manage to overcome your fears, you can take your hallucinations wherever you want.”[21]

In the 2010s, the output of works focusing on LSD has continued. These include a new edition of Albert Hofmann’s classic autobiography LSD: My Problem Child. Published in 2013, the year that marked the 70th anniversary of the discovery of LSD, the book is featuring a new translation by ethnobotanist Jonathan Ott and a foreword by Amanda Feilding. A year before he passed away, Hofmann asked Feilding if she could publish his seminal autobiography, and shortly before he died he approved Ott’s new translation.[22]

The history of LSD is in fact two parallel histories: One of them is a multifaceted subculture involving millions of people. The other has taken place in science and academia and has involved a comparatively very small number of scientists, study participants and psychiatric patients. After many decades of being more or less banned, scientific studies involving LSD were at last beginning to see the light of day in the twenty-first century. In 2014, the results of a historical LSD study conducted by Dr Peter Gasser near Bern in Switzerland between 2007 and 2012 were published in the Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. Gasser is the president of the Swiss Medical Association for Psycholytic Therapy, which were given permission to use LSD as a tool in psychotherapy in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Largely funded by MAPS, the pilot study was the first to be approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 40 years, and was conducted to examine safety and efficacy of LSD-assisted psychotherapy. Approved in 2007 and begun in 2008, it included 12 terminally ill patients separated into two groups. One group was administered 200 micrograms of LSD while the other group only received 20 micrograms. The low dosage group said their anxiety increased, while the higher dosage group said the LSD therapy had very positive effects on their anxiety.[23] The study, which evidently was a success, has received a lot of mainstream media attention with articles in Scientific American, The New York Times and The Huffington Post, to name a few. Incidentally, when Albert Hofmann heard that Steve Jobs regarded LSD as one of the most important things he had done in his life, he wrote a hand-written letter to the Apple co-founder in 2007 asking if he wanted to support the Swiss study.[24] Cleary, LSD’s return to science meant a lot to Hofmann.

In addition to the MAPS directed LSD study in Switzerland, another study receiving considerable attention is the Beckley Foundation’s pioneering LSD brain imaging study. Set up in 2009, the Beckley Foundation—Imperial College Psychopharmacological Research Programme is a collaboration established between Beckley Foundation director Amanda Feilding and Professor David Nutt, Head of Neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College London, with Dr Robin Carhart-Harris as lead researcher. The programme recently carried out the first fMRI and MEG research with LSD (which incidentally was purchased from a Swiss pharmaceutical company). The neuroimaging work was done at Cardiff University and included 20 participants of which 15 were men and five were women. After they were injected with 75 micrograms of LSD, a moderate dose, their brain activity was monitored.[25]

The team behind the study is currently in the process of analysing the data from the tests. In order to raise money for this work the Beckley Foundation turned to Walacea, a new crowdfunding site for scientific projects. Titled the “The World’s First Study of the Brain on LSD”, the campaign’s goal was to raise £25,000. When the campaign ended on 19 April this year, the very date that Albert Hofmann intentionally dosed himself with LSD for the first time, and which has become known by acid enthusiasts all over the world as “Bicycle Day”, the campaign had raised more than £53,000.[26] Needless to say, this is an impressive figure and if anything it shows that there is a renewed interest in LSD.

Other scientists who are doing LSD related work include researcher Teri Krebs of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, and clinical psychologist Pål-Ørjan Johansen. In 2012, the Norway based team published a retrospective meta-analysis of LSD as a treatment for alcoholism where they presented evidence for a beneficial effect of LSD on alcohol abuse. In addition to their scientific work, Krebs and Johansen recently started a non-profit organisation called EmmaSofia for the purpose of expanding access to MDMA and psychedelics. The organisation is also working towards making psychedelics legalised.

Compared with the “crisis” at the start of the new millennium, one could say there are signs of an LSD revival, at least when it comes to psychedelic science. However, it should also be said that the shortage of street acid that was seen in the early 2000s continues some 15 years on. Interestingly, it appears that it is especially hard to come across acid in the United States, the very birth-country of the LSD counterculture. A recent Reset.me article published 16 April, which marked the anniversary of the discovery of LSD’s psychedelic properties, even went under the blunt title “It’s Extremely Hard to Find LSD in the US – Here’s Why”. The article recounted the usual possible reasons to why it is so hard to come across street acid. These include the decade and a half old Wamego bust, difficulty in obtaining ergotamine, and the two decades old demise of the Deadhead scene.

The shortage of street acid is reflected in the entry pages of Erowid Center’s pill-testing program EcstasyData.org. Despite its name, EcstasyData.org publish test results of a wide range of drugs, including LSD. When browsing the lab results, LSD samples are scarce and far between. So far this year, there are only three entries of LSD. All three of the samples were blotters. One was bought online, while the other two originated from cities in the U.S. Interestingly, some of the samples tested between 2013 and 2014 contained higher doses than what was seen in the previously discussed 2005 Spanish analysis. A blotter originating from Spain that was tested in July 2013 contained 123,8 micrograms of LSD. Such doses are rarely found on blotter acid. Other Spanish blotters tested in 2013 contained between 52,1 and 81,9 micrograms. In addition, a blotter originating from Atlanta, Georgia that was tested in December 2014 contained 89,7 micrograms.[27]

In the early 2010s, there has been an unpredictable and troubling development in LSD culture, namely the appearance on the illicit drug market of a research chemical named 25I-NBOMe. It is still too early to say to what extent the drug will affect the street use of LSD, but there is no doubt that those using the latter will have to be more cautious of what they are ingesting. Just like LSD, 25I-NBOMe is distributed on blotter, and what is even more troubling is that there are several known instances where the drug has been sold as LSD or acid. In fact, 25I-NBOMe has even appeared on sheets featuring the classic Hofmann bicycle ride illustration. Unlike LSD, which has never resulted in any known pharmacological deaths among humans, 25i-NBOMe and other substances in the same group of chemicals, referred to as “25Is”, have already led to several fatal overdoses and prolonged hospitalisations in its very short time of recreational use.

Discovered by chemist Ralf Heim at the Free University of Berlin in 2003, 25I-NBOMeappeared on the illicit drug market around 2010, and is often referred to as a drug with similar effects to LSD. The drug has already been banned in several countries including Australia, Israel, USA, Sweden and Russia. Interestingly, critique against the 25Is, is also coming from within the psychedelic movement itself. For example, web forum Bluelight has posted a safety message, complete with skull and crossbones in a yellow triangle, stating that 25I-NBOMe carries “substantial risks that must be highlighted” and that the drug has killed at recreational doses. Unlike LSD, NBOMes are said to have bitter taste, hence the advice, “If it’s bitter it’s a spitter.” However, in order to be certain about the actual content of a drug, Bluelight urges users to use testing kits.[28] Furthermore, Erowid has included a note on their LSD page saying that blotter and liquid LSD being sold in 2013 in the US and Europe actually contained NBOMes. The Erowid website also contains a list of pharmacological (and a few behavioural) fatalities resulting from taking these research chemicals. Several of those who are included in the list took what they believed was LSD.[29]

The entry pages of EcstasyData.org contain samples of NBOMes, some of which were sold as LSD. For example, a blotter sold as LSD in Spain contained 25I-NBOMe.[30] Named “Bicycle”, this red and yellow sample tested in 2013 is clearly part of the upper right corner of a blotter sheet featuring the classic Hofmann bicycle ride illustration. Moreover, a 2012 test of a liquid sold as LSD in Wisconsin showed that it contained 2C-NBOMe.[31] Seeing that the appearance of counterfeit acid will probably continue, the work carried out by EcstasyData.org and other similar harm-reduction websites will continue to be hugely important.

Needless to say, the appearance of 25Is presumably has had a psychological effect on most LSD users. Before the NBOMes, the worst that could happen when taking LSD was having a difficult, or even traumatic, experience. Today, LSD users stand the risk of unknowingly taking a completely different drug that may lead to a fatal overdose or hospitalisation. Rarely has Timothy Leary’s old motto “Just Say Know”, or good old advice such as “Know Your Source”, been more appropriate as when it comes to contemporary use of street acid. Only time will tell what will become of these research chemicals. If enough users realise the risks associated with these drugs and stop using them, they might be reduced to a short episode in twenty-first century illicit drug culture. However, if the War on (some) Drugs continues, there may turn up new substances that are equally, if not more, problematic as the NBOMes.

New technology often brings with it new behavioural patterns. This has also affected the way LSD is being sold. Before the millennium LSD was often traded at rave parties, music festivals and concerts, but in the 2010s the drug also became available online. The most well-known marketplace for drugs, including psychedelics such as LSD, was Silk Road. The online black market existed on and off between 2011 and 2014 and was operated as a Tor hidden service, which enabled users to browse the site anonymously. Of the 10,000 products for sale by vendors in March 2013, 70 percent were drugs.[32] Although Silk Road has been shut down, the online sale of LSD continues on the Darknet.[33]

The draconian laws for manufacturing or selling LSD persist throughout the world. But the twenty-first century has also seen a wave of decriminalisation of recreational drugs, including LSD, for personal use. For example, as of January 2010, drug users in the Czech Republic can possess small doses of various psychoactive substances. When it comes to LSD, the possession of up to 5 doses is considered a mere misdemeanour offense, which, should the user get caught, would lead to a fine equal to a parking ticket.

Few other psychedelics have been as widely discussed as LSD, yet it has been a very long time since the drug was the main driving force behind the psychedelic movement. Instead psychonauts of today tend to use a number of different substances including psilocybin mushrooms, DMT, Salvia, Ketamine, MDMA and 2-CB to name a few. In addition, over the course of the twenty-first century ayahuasca has spawned a movement of its own, which has received a substantial amount of mainstream media coverage. Although several of these mind-altering substances were around already in the 1960s and the 1970s, they were not as widely used. For example, very few hippies in the early counterculture had experimented with ayahuasca.

In his 2012 piece “What can entheogens teach us?” writer James Oroc mentions how different psychedelics are viewed in the contemporary psychedelic movement. Interestingly, it seems Hofmann’s potion is approached with caution even among psychonauts. Many of the 20 somethings that Oroc talks to at festivals “seem to love DMT but are terrified of LSD having already experienced a trip too long and arduous for them … and they probably ate a quarter of what their parents did for their first time in the 60’s!”[34]

In trying to understand LSD’s place in the contemporary psychedelic movement, one also needs to consider the hugely influential writer and speaker Terence McKenna. Despite the fact that he has been dead for a decade and a half, he still has a considerable following, and many of his die-hard fans keep his ideas alive on social media. In fact, had it not been for McKenna it is questionable if psilocybin mushrooms and ayahuasca would have become as widely used as they are today.

His strong focus on plant based psychedelics clearly brought less focus on LSD – a semi-synthetic substance manufactured by a chemist in a laboratory – and it is likely that his views have affected how people look upon LSD. When it came to the latter, he simply did not seem impressed by it. For example, in one of his workshops McKenna said that, “LSD is like psychoanalytical Drano. It’s not a personality.”[35] Instead, he was drawn towards psilocybin mushrooms, which he talked of as having a “voice”, and ayahuasca, which is referred to as “Mother Ayahuasca” (i.e. a “she”)

by many of its users. Admittedly, associating psychedelics with personality is tricky. After all, what people experience on mind-altering substances is highly subjective and varies considerably among different individuals. That said, it is safe to say that very rarely is LSD referred to as having a “voice”, or as a “mother” or a “she”, by its users. This supposed lack of personality is not necessarily to LSD’s disadvantage though. Instead, seeing that there is no personality getting in the way, it may be exactly what makes it suitable to applications such as problem-solving or exploring the arts. Although LSD can lead to deeply spiritual or religious experiences, it is safe to say that the drug is less associated with the New Age spirituality (no negative connotation intended) that is increasingly seen in contemporary psychedelia.

Andy Roberts was probably right when he wrote that LSD seemed like yesterday’s drug in the early twenty-first century. During the MDMA craze of the 1990s, which continued into the new millennium, it is probable that many young people thought of LSD as an old hippie drug. However, it seems that every time acid is starting to become a thing of the past, something happens that brings it back into contemporary culture. At the moment, that “something” includes Beckley Foundation’s current brain imaging study on LSD.

According to psychedelic researcher Teri Krebs, people have used “at least half a billion doses over the years”.[36] However, despite the fact that huge numbers of people have taken acid, exceptionally few speak openly about their experiences. Even within contemporary psychedelia there are very few outspoken acid advocates. This is not to say that there are no exceptions. For example, in her piece “There is no hiding with LSD” published in The Guardian in 2011, writer and lecturer Dr Susan Blackmore described LSD as “the ultimate psychedelic”.[37] But even if most people still speak in a hushed tone about LSD, its legacy is huge, and as most acidheads can verify its influence is seen pretty much “everywhere” in our western culture.

So, even with draconian laws and strict controls of ergot alkaloids, it is highly unlikely that LSD will disappear in the foreseeable future. As we all know, governments all over the world have tried to stamp out LSD ever since its ban in the 1960s. Yet it is still here, just like cannabis, another “evil” that the powers that be often tend to demonise. And as long as humans feel compelled to enter altered states of consciousness for the sake of ecstasy, healing, mind-exploration, problem-solving, or simply for cosmic entertainment, LSD will most likely continue to be used.

Why not learn more about LSD and psychedelics by picking up a copy of the Psychedelic Press UK bimonthly Journal?