If there’s any truth to Terence McKenna’s Stoned Ape theory, then human evolution may owe a great debt to psychedelic microdosing — the practice of taking a sub-perceptual dose (an amount too small to produce traditional psychedelic effects) of a substance such as LSD or psilocybin.

As those who have read McKenna’s Food of the Gods know, the author famously proposed that our species’ collective journey from Homo erectus to Homo sapiens may have begun with early pack-hunting primates taking low doses of psilocybin mushrooms to improve their hunting abilities.

According to author James Oroc, the practice of microdosing for improved visual acuity, energy and quick response time is alive and well in the present day, especially among certain extreme sports enthusiasts.

“Virtually all athletes who learn to use LSD at psycholytic [low to medium] doses believe that the use of these compounds improves both their stamina and their abilities,” Oroc wrote in the spring 2011 edition of the MAPS Bulletin.

Athletic prowess aside, numerous experimenters and research subjects have claimed that sub-threshold doses of psychedelics have improved their overall wellbeing and/or alleviated specific conditions like depression and cluster headaches.

Others, such as a couple of commentators on a thread about microdosing on Reddit.com, have used psycholytic doses as a problem-solving aid.

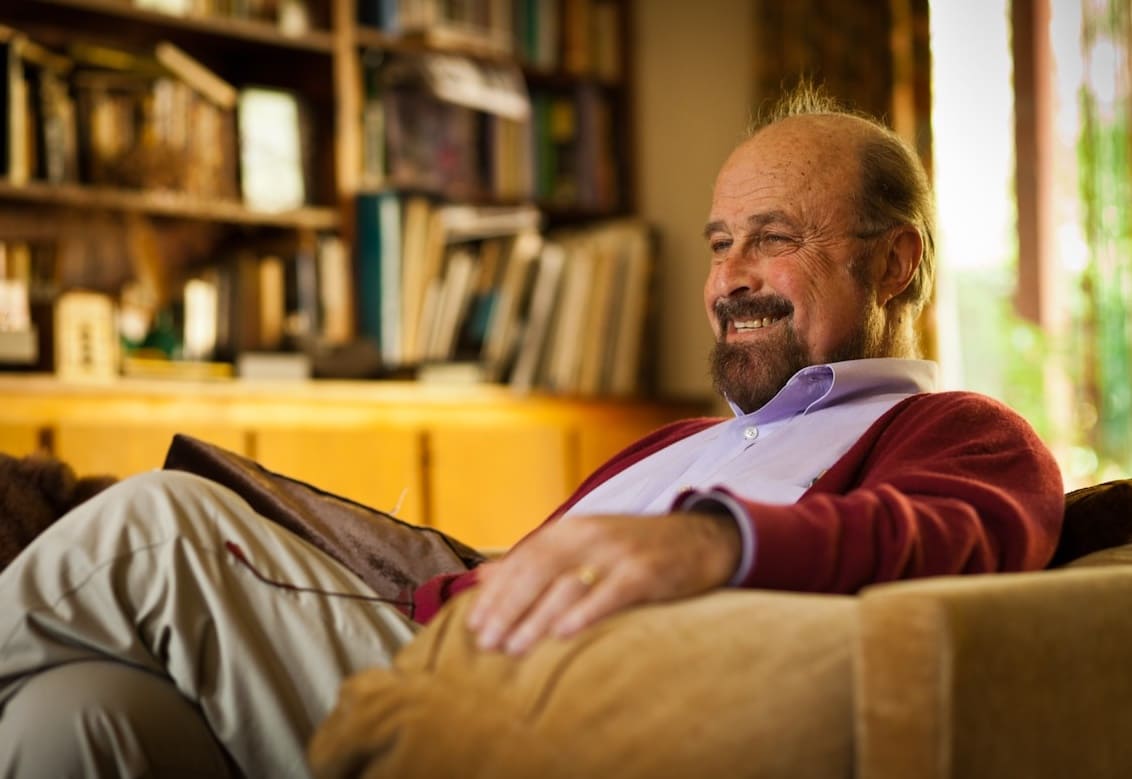

Dr. James Fadiman, Ph.D., who was part of a Menlo Park, California-based team of researchers who studied the use of psychedelics in problem-solving in 1966, has been looking into the effects of microdosing since 2010. “[This practice] appears to improve practically everything you do a little bit,” Fadiman told Reset. “Various people have said they’re more comfortable with what they’re doing, and they do it a little better.”

Participants in Fadiman’s studies initially contact him at [email protected]. He responds by sending a protocol that essentially consists of a suggestion that prospective participants microdose every fourth day for a month and make notes of how they are feeling from one day to the next.

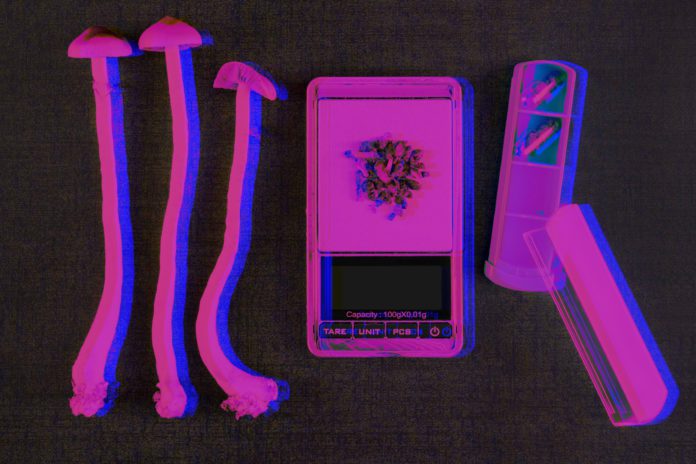

Fadiman does not provide participants with psychedelics; rather, he offers information and guidelines to help maximize the microdosing experiences of subjects who already have their own materials. In this way, Fadiman has collected approximately 30 reports ranging in length from three paragraphs to between 30,000 and 40,000 words.

In a chapter of Fadiman’s book The Psychedelic Explorer’s Guide titled “Can Sub-Perceptual Doses of Psychedelics Improve Normal Functioning?,” one study participant describes a dose of 10 to 20 micrograms of LSD as both a stimulant and a calming agent.

According to her notes, microdosing seems to augment her wit, response time and visual and mental acuity. “Sub-doses of 10 to 20 micrograms allowed me to increase my focus, open my heart, and achieve breakthrough results integrated within my routine,” her report reads.

This improved focus and clarity can be especially useful to artists, writers and other people working in creative fields. “What people report about doing their creative work is that they’re not creating at a higher level, but they’re creating longer; they’re in the flow for longer,” offered Fadiman, who also gathers data about microdosing from a conversation thread about low doses of LSD on Bluelight.org.

He added that he knows of two noted writers who have used sub-perceptual doses of psychedelics while writing the first drafts of every chapter of their most recent books.

Along with being what one study participant has called an “all-chakra enhancer,” microdosing shows promise in treating cluster headaches, the pain of which is said to exceed that of childbirth and kidney stones.

Through his work with a group called Clusterbusters, Fadiman has come in contact with a number of cluster headache sufferers who have found relief from this condition through the use of LSD and mushrooms after all other treatments have failed. While the doses that such sufferers use to treat their headaches are generally too large to be considered sub-perceptual, Fadiman mentioned one subject who used a microdose of LSD to get rid of an “ice pick headache” (so named because its pain has been compared to that of an ice pick going into one’s skull) within five to 10 seconds. That subject achieved the same result several times over the next few months. Since then, her headaches have ceased.

Several research participants have also told Fadiman that microdosing alleviated their depression. One such subject, a Parkinson’s disease sufferer, reported that after a month of microdosing with LSD, his Parkinson’s symptoms were not improved, but his underlying depression was. Fadiman stressed, however, that because the data he has collected in this area is based on month-long microdosing periods, he doesn’t yet know whether this practice can yield long-term depression relief.

If future studies show microdosing to be as effective a depression reliever in the long-term as it appears to be in the short-term, then it may prove to be a viable alternative to prescription mood stabilizers, many of which are highly addictive. In light of their energizing and focusing effects, sub-perceptual doses of psychedelics may also provide a suitable replacement for anti-ADHD medications and other such pharmaceutical cognitive enhancers. Lending credence to this notion, one participant in Fadiman’s studies recently reported that microdosing helped him wean himself off of Adderall, a notoriously addictive anti-ADHD drug also used by many college students during all-night study sessions.

Paraphrasing Carl Hart, Ph.D., a professor of biochemistry at Columbia, Fadiman offered, “Adderall is no different than street amphetamine made in the back of someone’s car. So the drugs that rot your brain and that we’re busting people for doing these terrible things [on] are the same drugs we’re giving to hundreds of thousands of children every morning.”

Expounding the addictive properties of certain prescription drugs, Fadiman observed, “As a general hint, if it says, ‘Do not miss a dose, and do not try to stop this medication without medical help,’ you know that you have a drug which is hard to get off of. It’s a very tricky area, because the pharmaceutical industry seems to not worry about this problem. In fact, there’s a term in the medical literature when you’re trying to get off of one of these substances. It isn’t called ‘withdrawals,’ as it is for illegal drugs; it’s called ‘tapering.’”

He added that this tapering can be a lengthy process: some patients taking extended-release capsules filled with a couple hundred microdots each have weaned themselves off these drugs by decreasing their intake by a single microdot every few days or even every week.

Albert Hofmann, the Swiss chemist who discovered LSD, is known to have been a proponent of microdosing as an alternative to the anti-ADHD stimulant drug Ritalin (called “one of the most abused drugs in the U.S.” by the website AddictionHope.com). It is extremely likely that Hofmann, who regularly microdosed with LSD in the last few decades of his life and considered this practice the most under-researched area of psychedelic use, would have thought sub-threshold doses of psychedelics to be an equally viable replacement for newer anti-ADHD amphetamines like Adderall or Vyvanse. Both do not come without very dangerous side effects. Web MD lists a myriad of negative side affects for both drugs. Among these are chronic trouble sleeping, heart throbbing or pounding, sexual problems, aggression, abnormal heart rhythm, heart attack, high blood pressure, trouble breathing, stroke, mental impairment, and seizures — to name but a few.

Citing several study subjects’ claims that microdosing has helped them get off of prescription antidepressants, anti-anxiety medications, mood stabilizers and cognitive enhancers, Fadiman said he is hopeful that sub-perceptual doses of psychedelics will yield the benefits of such medications without their dangers and negative side effects. He added, however, that all official studies in this area will need to take place in universities, because “pharmaceutical companies are not about to test their own products against something that 1) is illegal and 2) might be better.”

In addition to helping people break their dependency on FDA-sanctioned drugs, microdosing shows promise in helping treat addiction to illegal substances. Representatives from one treatment center in Mexico have told Fadiman that after using ibogaine to help rid patients of substance abuse problems, they suggest that these patients take microdoses of that compound for a few months “to hold their gains.”

Given the positive feelings that many people experience while microdosing, some question has arisen as to whether this practice could itself become addictive. In Fadiman’s view, it is unlikely that anyone will become physically dependent on compounds that are inherently anti-addictive — if you take the same psychedelic substance every day, it stops working.

“Let’s say you take a high dose on Monday,” he proposed. “If you take the same dose on Tuesday, you get a very little effect, and if you take the same dose on Wednesday, nothing happens. It’s as if your system says, ‘No, I really can’t take any more of whatever those effects are until we’ve cleaned out the system.’”

While the research thus far seems to indicate that microdosing is not harmful or dangerous, a few of Fadiman’s subjects have reported unpleasant effects: one discontinued the practice because she felt it was bringing up too much emotion, while two others have observed that they sweat more than usual on days when they microdose. Both of the subjects who complained of excessive sweating — one of whom was using LSD and the other mushrooms — were unsure whether the sweating was part of healing or just a quirky side effect. One of these two participants reported that she was thrilled with the increased productivity and sense of calm that she got from microdosing, while the other found the practice useful, but was bothered by the sweating.

While microdosing does not induce the same kinds of spiritual breakthroughs that higher doses of psychedelics can, Fadiman observes that over time, it produces effects much like the after-effects of such breakthroughs. “People are saying, ‘After a month or more of microdosing, I’m eating better; I’m nicer to my kids; I’m not as upset when people behave badly,’” he notes. “One man was saying, ‘I’m so much more in the present. I used to, even when I was enjoying something, really be thinking about what I was going to do when it was over and so forth. Now when I’m doing something, I’m actually doing it.’”

He added that microdosing appears to give people a better orientation to themselves. “I think it’s a little bit [like] the way people indicate that if you would only do meditation in the morning and do some yoga and eat healthy, your whole life would improve,” he noted. “It looks like microdosing is in that direction.”