After more than 30 years in which psychedelics were considered dangerous remnants of the 1960s, the drugs have begun to make a comeback, this time as potential remedies for a host of tough-to-treat maladies. Pilot studies and clinical trials of LSD, psilocybin, ketamine and MDMA have shown that the drugs, often in combination with talk therapy, can be given safely under medical supervision and may help people dealing with opiate and tobacco addiction, alcoholism, anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD.

That these investigations have shown potential is not surprising to many researchers. A generation of scientists and practitioners had used psychedelics successfully with thousands of patients until the research was banned in 1970, after the drugs were embraced by an exploding counterculture that seemed to threaten the status quo.

In the panicked reaction, psychedelics were listed along with heroin in the highest rungs of prohibition. Ironically, this failed to stop recreational use but it shut the science down cold. As one researcher put it, “It was as if psychedelic drugs had become undiscovered.”

In the panicked reaction, psychedelics were listed along with heroin in the highest rungs of prohibition. Ironically, this failed to stop recreational use but it shut the science down cold. As one researcher put it, “It was as if psychedelic drugs had become undiscovered.”

But a small cadre of psychiatrists and researchers, often risking careers and reputations, pushed to bring psychedelics back to the lab and the clinic. Their persistence paid off. Beginning in the 1990s, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first human clinical studies of psychedelic drugs in a quarter of a century. By 2004, the first FDA-approved trial of the medicinal use of a psychedelic drug, in this case a trial of MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD involving 24 subjects, was underway. Now such studies are proliferating.

“For more than 30 years I have been working to make FDA approval of psychedelic psychotherapy more than a dream,” says Rick Doblin, founder and director of the nonprofit Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies. “Now that castle in the air has a foundation underneath it and is becoming an impending reality.”

How LSD began

The modern investigation of psychedelics began with the accidental discovery of the consciousness-altering properties of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD was its German acronym) by Albert Hofmann, a chemist for a Swiss pharmaceutical firm. Hofmann had been looking for a compound that might stimulate circulation and respiration when he combined derivatives of rye fungus and ammonia. Initial animal testing turned up nothing of note, except a strange restiveness in the animals.

But for reasons Hofmann could explain only as an “odd presentiment,” he resynthesized the compound five years later, in 1943, accidentally exposing himself to it and going on history’s first LSD trip. “In a dreamlike state, with eyes closed,” Hofmann wrote, “I perceived an uninterrupted stream of fantastic pictures, extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colors.” He correctly understood that such a dramatic alteration of consciousness by a chemical would be of great interest to the young science of psychiatry.

By the mid-1950s, researchers had experimented with administering LSD and natural psychedelics such as mescaline (from the Mesoamerican peyote cactus) to facilitate talk therapy for a wide variety of psychic ailments. Trials involving hundreds of patients and thousands of doses of psychedelics were conducted in Europe, Canada and the United States, and most investigators reported positive and in some cases almost miraculous results.

In 1954, psychiatrists at an English hospital set aside an entire ward for conducting LSD therapy with patients who had severe, chronic, treatment-resistant mental illness. They concluded that 61 of 94 patients improved or even completely recovered after six months.

In 1960, a physician named Sydney Cohen surveyed the findings of 44 physicians who had administered 25,000 doses of LSD or mescaline to 5,000 people under widely varying conditions. Cohen found “no instance of serious or prolonged physical side effects” or any evidence of addictive potential either in those trials or in the wider literature on psychedelic drug studies. He did find adverse psychological reactions — including acute anxiety and psychotic breaks — but determined that they were rare and mostly related to preexisting mental illnesses.

“Considering the enormous scope of the psychic responses it induces,” Cohen concluded, “LSD is an astonishingly safe drug.”

Revolutionizing psychiatry

As LSD and its cousin compounds were revolutionizing psychiatry, they were also igniting a new science. Within just a few years of Hofmann’s discovery, chemists were surprised to learn that a substance in the blood called serotonin, which was known to contract the muscle of the small intestine and constrict blood vessels, was also found in the brain. They had no idea what it did there until, in 1954, a researcher noticed that the chemical structure of serotonin bore a likeness to that of LSD. The similarity of the two molecules, coupled with the known power of LSD to alter how people think and feel, switched on the light that some researchers believe inaugurated the modern science of the brain.

Research made it clear that serotonin affected mood and thoughts, and that LSD and other psychedelic drugs worked by somehow altering the way the brain processes serotonin. Serotonin turned out to be one of many substances that regulate and facilitate brain activity; these substances are called neurotransmitters because they help transfer signals from one brain neuron to the next. Serotonin was far less abundant than other neurotransmitters, but it appeared to have outsize impact, involving itself in the regulation of appetite, sleep, memory and learning, temperature, mood, behavior, muscle contraction and function of the cardiovascular and endocrine systems.

Because psychedelic molecules are physically similar to serotonin, the two fit into the same receptors in the brain, like two keys in a lock. The specifics of how psychedelics interact with serotonin receptors to produce a mind-altering trip remain mysterious and disputed. The most interesting clues have come from studies using functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI, a relatively new technology that depends on the magnetic properties of blood flow to create pictures of a brain in operation.

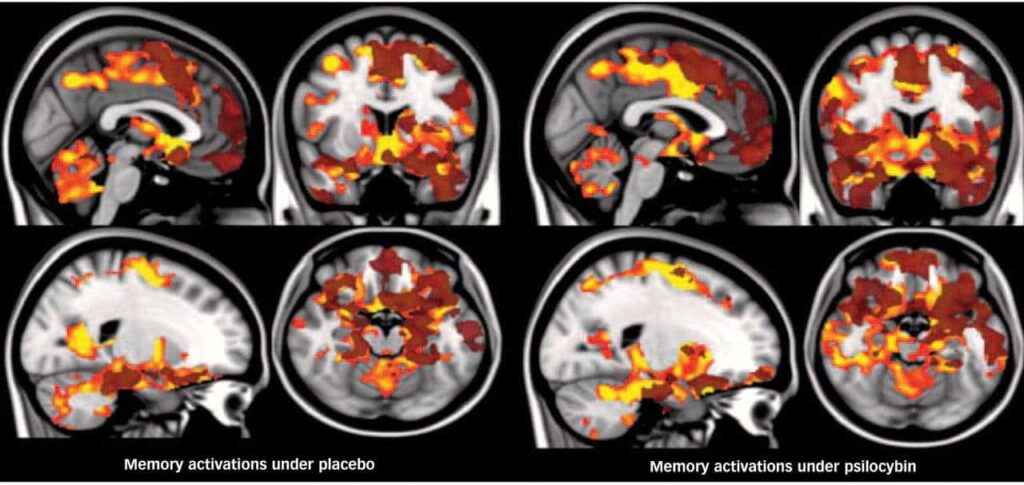

In 2012, researchers at Imperial College London published results of a study in which they injected volunteers with psilocybin and then observed their brains via fMRI. Given the psychedelic experience’s well-known assault on the senses — flashing visual patterns, intense colors, enhanced sounds, overwhelming visions and emotions — the researchers expected to see increased brain activity, which some earlier scans had found.

Brain effects

Instead, their screens registered decreased activity, which seemed like a mistake until it was confirmed by another fMRI scan and correlated with the participants’ reports: The larger the decrease in brain activity, the more intense the psychedelic experience.

The decreased activity was not uniform throughout the brain. Task-oriented areas of the brain, such as those associated with seeing and moving, had only nominal decreases. But areas of greater complexity — those associated with self-image, introspection and imagining past or future events — showed large decreases in activity. This linked nicely with the reports of the subjects, who did not have significant motor impairment but talked about experiencing a loss of ego, an increased sense that objects had unusual significance and dramatic alterations in their experience of time.

The researchers noted two intriguing connections with other studies: A brain on psilocybin bore a striking resemblance to the brain of an experienced meditator during deep meditation. And the areas of the brain with decreasedactivity caused by psilocybin were the same regions that showed chronicallyincreased activity in people with clinical depression.

“We’re motivated to think of the potential of this drug more seriously through the brain imaging results,” said Robin Carhart-Harris, lead researcher in the Imperial College study. “Regions which are reliably overactive in depression are deactivated by psilocybin . . . and that fits with the anecdotal reports of users of psychedelic drugs who feel a renewed ease with life after an experience, less burdened by everyday stresses.”

What Carhart-Harris found even more interesting than the raw activity levels was the relative activity of different brain areas that seemed to be working in concert, rather than in opposition. Research using fMRI scans during normal consciousness reveals that when the introspective part of the brain — the part that organizes thoughts of self — is active, the part that scrutinizes the outside world quiets, and vice versa. But after administration of psilocybin, those areas move up and down together. Could this lock step between the introspective and external focus be related to the feeling of “oneness” with the world that people who have taken psilocybin often use to describe their experience?

Relating specific experiences to general changes in brain activity is a dicey business, made even more so because the basic reliability of fMRI interpretations is controversial. (One researcher famously demonstrated that fMRI data could show brain activity in a dead fish.) Nonetheless, the fMRI results have been useful in explaining why psilocybin, and by extension other psychedelics, might help improve mental health.

In 2004, Michael Mithoefer, a psychiatrist in Charleston, S.C., was the first to win FDA approval for clinical studies using MDMA — known informally as ecstasy — to treat PTSD.In the treatment manual he created, Mithoefer urges therapists not to attempt to direct the session, but to concentrate on creating an atmosphere of safety, openness and trust in the patient’s own “inner healing intelligence,” which “the medicine” — the MDMA — somehow activated. It might sound like hocus-pocus, but Mithoefer explained it this way:

“When I worked in the ER, somebody came in with this big gash on their arm full of gravel. I don’t know how to heal that. My job is to create favorable conditions for the inner healing intelligence to be able to do it — so get the gravel out, bring the sides closer together, irrigate it, and then the body always moves towards healing. What can happen is that things get in the way: infection, not enough blood supply, a foreign body left in there. So in a way, our job in the ER is to remove the obstacles [to healing].

“I think it’s very much the same with the psyche. I think there is this movement toward healing, and there’s a lot that can get in the way of that.”

Torsten Passie, a German researcher who is a visiting professor of psychiatry at Harvard, has developed an intriguing link between recent neurobiological research and Mithoefer’s idea that MDMA enables the mind to move naturally toward healing.

Bad memories

Under normal circumstances, research has shown, sights, sounds, scents and sensations from our sensory organs enter a region at the center of the brain called the thalamus. The thalamus distributes that data to the more sophisticated brain regions involved with conscious thought. The processed material — sorted for context and assessed for significance — is returned to the thalamus, which then deposits it into the hippocampus, where it is stored as memory.

In the case of a severely traumatic experience such as rape or combat, the higher brain’s ability to process is overwhelmed, according to Passie, and a more primitive method for storing memory takes over. The sensory memory of the trauma — which is still entangled with the emotion associated with that moment — passes through the thalamus and is stored directly in the hippocampus without processing in the more sophisticated parts of the brain.

These raw memories, still tied to the fear response they provoked, are a constant threat to bolt into awareness as flashbacks, nightmares, hypervigilance or rage, which can trigger the fight-or-flight reflex centered in the amygdala. The amygdala, Passie says, acts as a guard, attempting to suppress the unprocessed traumatic memory and keep it from barging into consciousness. It’s not a healthy arrangement. The constant tension of having the nasty secret hidden in the brain’s basement poisons the psyche, which flails around in pain, creating PTSD’s self-destructive symptoms.

Brain scan studies support the idea that the repressive amygdala is overactive in people with PTSD, while the rationalizing power of the higher brain is suppressed. Studies also show the opposite is true for someone given MDMA; the drug stimulates the prefrontal cortex and suppresses the amygdala. (These results line up with the reports of people in MDMA clinical trials. One of the drug’s signature effects is a dramatic reduction in fear, a sense of “being protected,” coupled with a rapid-fire run of novel insights.)

Passie theorizes that as the amygdala lets down its guard under the drug’s quieting influence, the traumatic memories can reemerge from the hippocampus to be sent up for the higher processing the brain didn’t do in the immediacy of the trauma. The reprocessing is assisted by the tide of hormones MDMA causes to be released; cortisol, which is associated with emotional learning; and oxytocin and prolactin. These hormones are also released in similarly large quantities immediately preceding and following orgasm — an event known to engender powerful feelings of intense emotion, security, closeness and well-being — exactly the mental states known to promote breakthroughs in psychotherapy. Now, at last, the conditions exist in the brain that allow traumatic memories to be properly contextualized and integrated into the personality in a healthy way.

A crayon drawing

While Passie is encouraged by the advances in understanding made possible by brain scan research, he cautions that the science is still in its infancy. There’s no guarantee that these theories will hold when more, larger studies are conducted. “This is more like a crayon drawing of brain function than an oil painting,” he says.

Meanwhile, the accumulating clinical experiences in trials of psychedelic therapies point to a broader understanding of why they might be effective. In a recent study in which psilocybin was given to 15 recidivist smokers, 80 percent managed to remain smoke-free six months after the 15-week treatment. The study’s lead author, Matthew W. Johnson, an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, was quoted as saying that “quitting smoking isn’t a simple biological reaction to psilocybin, as with other medications that directly affect nicotine receptors.” Instead, Johnson said, what changed the smokers’ behavior was the subjective experience they had when taking the psilocybin: “When administered after careful preparation and in a therapeutic context, psilocybin can lead to deep reflection about one’s life and spark motivation to change.”

This observation is similar to what psychiatrists Humphry Osmond and Abram Hoffer concluded in the 1950s when they had great success using LSD therapy to help alcoholics stop drinking. Hoffer and Osmond’s treatments proved successful enough that the Canadian government at one point in the early 1960s briefly determined that LSD was no longer an experimental treatment for alcoholism but one that had proved effective.

“As a general rule,” Hoffer wrote, “those who have not had the transcendental experience are not changed; they continue to drink. However, the large proportion of those who have had it are changed.”

Shroder is the author of “Acid Test: LSD, Ecstasy, and the Power to Heal” (Blue Rider Press), from which this article is adapted.