Thanks to the tireless efforts of researchers determined to study these controlled and controversial substances, research on the therapeutic applications of psychedelics is underway for the first time in decades. The medical uses of these substances to promote healing are just the beginning of their reintroduction into our society. The ability of psychedelics to treat depression, anxiety-related conditions and substance dependence is establishing respect and recognition of their usefulness and is helping to shift the discourse toward more rational and evidence-based approaches. However, their ability to stimulate creative thinking and facilitate problem solving may be next in line to capture our imaginations.

As Stanislav Grof recounts in his 1980 book LSD Psychotherapy, the potential of psychedelics to enhance the creative process was noted by LSD therapists in the 1950s and 60s, and the subject was explored comprehensively in Robert Masters’ and Jean Houston’s 1968 book Psychedelic Art. Many artists who participated in these studies found that their psychedelic experiences left them with access to deep sources of inspiration and helped them achieve greater degrees of originality and artistic freedom. It also wasn’t rare for their professional colleagues to note an improvement in the quality of their work.

Creative benefits like these weren’t limited to professional artists; Grof notes that, during psychedelic sessions, people tend to explore various forms of expression, such as drawing or poetry. The product can be impressive due to the emotional intensity of the experience, as illustrated by this series of self-portraits drawn by a woman during an LSD session. Experimenting with different forms of expression during a trip can lead people to find a new creative outlet that they start to pursue regularly, which can be very beneficial regardless of whether they show initial talent.

Others discover new ways to appreciate and engage with various art forms, which can similarly open up new dimensions of experience. Grof points out in LSD Psychotherapythat a single LSD session in people who were indifferent to “non-conventional art forms” could develop deep insight into a variety of more abstract art forms including cubism, impressionism, and surrealism. In an interview on drugs and creativity, Aldous Huxley made a similar point on how these experiences can show us how different artists naturally see the world: “It does help you to look at the world in a new way. And you come to understand very clearly the way that certain specially gifted people have seen the world. You are actually introduced into the kind of world that Van Gogh lived in, or the kind of world that Blake lived in.”

In LSD Psychotherapy, Grof also notes that these applications might extend beyond the realm of art, to scientific disciplines. At times, scientists who participated in Grof’s LSD training program seemed to gain “access to vast repositories of concrete and valid information in the collective unconscious,” with these sessions leading to new insights in fields as diverse as genetics, anthropology, philosophy, psychology, and subatomic physics.

In addition, LSD appeared to facilitate novel and unexpected approaches to problem solving, as well as the occurrence of intuitive flashes of insight in which fully-formed solutions and new directions of exploration were often received. This was especially the case with participants that had a high degree of knowledge and intellectual capacity. The chances of bringing back useful information are increased by being knowledgeable in one’s field of specialization, with the ability to ask relevant questions and use appropriate terminology to describe the results.

Similar reports are provided in Jeremy Narby’s essay “Shamans and Scientists” (published in Charles Grob’s 2002 book Hallucinogens: A Reader), which tells of three molecular biologists who, in pursuit of biomolecular knowledge, traveled to Peru in 1999 to take ayahuasca with an experienced shaman. Two of them were university professors and researchers while the third was a scientist working at a genomics company, and each brought questions related to their research that would guide their intention in the ayahuasca sessions. In these sessions, they experienced visions of DNA, chromosomes, and various molecular and cellular processes, and they obtained novel insights and answers relevant to their research questions and fields of specialty. The scientists agreed that the ayahuasca session had given them new ways to access and synthesize things they already knew on various levels.

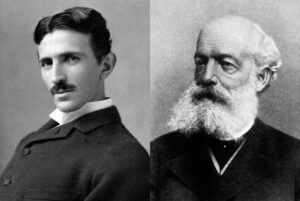

It’s relevant to note that many major developments and solutions in science have resulted not from logical reasoning but from a flash of insight during a moment of suspended rationality. Despite the widespread idea that science advances solely through logic and reason, there are many famous cases in which a discovery or solution came through a vision, dream, or some other altered state: The final design of the electric generator came to Nikola Tesla in detail in a vision; August Kekulé realized the atomic structure of benzene, which consists of six carbon atoms arranged in a hexagon, after he dreamed of a snake biting its own tail. As Grof notes, the occurrence of these intuitive flashes in normal waking consciousness is unpredictable, which makes the possibility that psychedelics might facilitate this type of processing a highly intriguing one.

In 1966, James Fadiman and other researchers at Stanford University decided to studythis possibility more closely, this time using mescaline. Professionals were selected from various fields that regularly require creative problem solving, including engineering, architecture, mathematics, physics, and psychology. Each participant was asked to bring problems with which they had struggled for weeks or months without obtaining a satisfactory solution, and which they could attempt to solve during the psychedelic session.

The results of this study were very promising. Many of the participants arrived at solutions that were later accepted for construction or implementation, and others discovered new directions for further investigation. They reported that the psychedelic had facilitated the creative process in a number of ways, including lowering anxiety and inhibitions, enhancing flexibility of thought, heightening visual imagery and fantasy, and providing access to unconscious information. They also reported high levels of focus and concentration, heightened empathy with people or with the processes and objects being contemplated, and the ability to clearly visualize the completed solution. This article offers a great overview of Fadiman’s research on creativity. Research conducted by Oscar Janiger on enhancing creativity with psychedelics showed similarly positive results.

While the results were certainly promising, this area of investigation was brought to a halt once psychedelics were made illegal. Despite this, many people continue to use psychedelics for these effects.

Recently, CNN shone a spotlight on psychedelic use in Silicon Valley by tech entrepreneurs, engineers, and software developers to enhance creativity and problem solving. In the article, entrepreneur and investor Tim Ferriss says the billionaires he knows are regularly taking psychedelics “to be very disruptive and look at the problems in the world … and ask completely new questions.” Similarly, a college friend of Steve Jobs remarks that Jobs was drawn to psychedelics for their effects on creativity. Steve Jobs himself described taking LSD as profound and “one of the most important things in my life,” something that he said drove him to create and contribute to history and human consciousness.

In a 2008 article in the Journal of Psychopharmacology, Dr. Ben Sessa proposes that it’s time to revisit the role of psychedelics in enhancing human creativity. While these drugs have a contentious history, their safety has gained more recognition in recent years. And if psychedelics can indeed enhance creativity, we stand much to gain collectively from pursuing this research. In addition to expanding our neuroscientific understanding of creativity, Dr. Sessa argues that there would be vast implications for commercial industry, as most of it relies on product design and marketing, in which creativity is integral. In addition, Grof notes that the effects of psychedelics on creativity can help not only to discover solutions to specific problems, but also to bring about entirely new paradigms that revolutionize entire disciplines.

Dr. Sessa’s suggestion may be close to becoming reality. Recently, a crowdfunding campaign by the Beckley Foundation quickly raised £25,000 ($37,000 USD) to conduct the world’s first imaging study of the brain on LSD. After meeting their goal, they extended the campaign and raised an extra £28,000 ($42,500 USD) to conduct a study on how LSD influences creativity.

With luck, the Beckley Foundation’s study will be the first of many such investigations, as there remains much to be discovered about the usefulness of psychedelics as tools to stimulate creativity. As we’ve seen, the work conducted by psychedelic therapists and researchers thus far points to the potential for making artistic experience and expression more accessible, moving us toward wholeness as we become open to more aspects of ourselves. In addition, the possibility of reliably stimulating innovative thinking and problem solving in our greatest minds could bring unimaginable solutions and innovations to the problems faced today. For, as Terence McKenna said, “our world is endangered by the absence of good ideas.”