25 February 2015 — This article has been updated to better reflect the limitations of the study.

A new species of lichen has been discovered in the Ecuadorian Amazon rainforest, according to a recent paper published in The Bryologist. Researchers led by lead author Michaela Schmull have tentatively identified tryptamine and psilocybin in the lichen, among other potential substances.

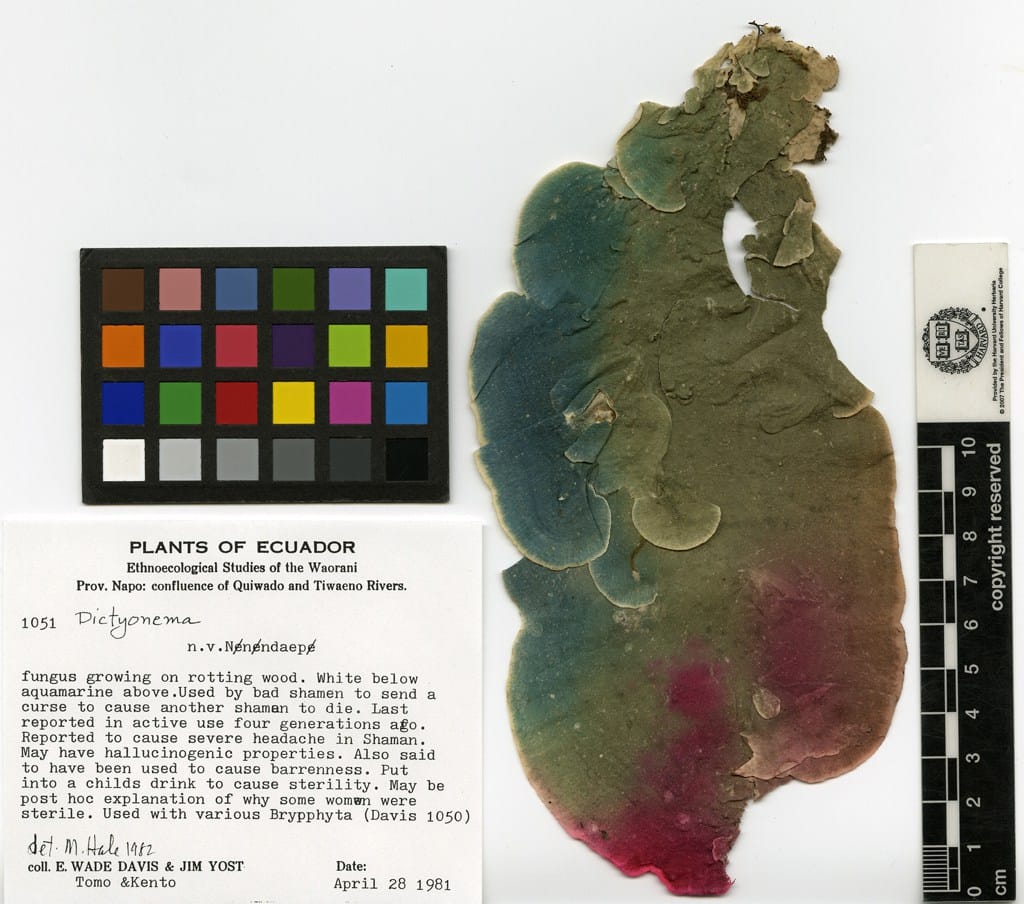

The story is a rather unusual one. There is only one known sample of the lichen in all of Western science, and it was collected in 1981 by ethnobotanists Wade Davis and Jim Yost while conducting research in Ecuador. In a 1983 paper describing their discovery of this lichen, Davis and Yost write:

In the spring of 1981, whilst we were engaged in ethnobotanical studies in eastern Ecuador, our attention was drawn to a most peculiar use of hallucinogens by the Waorani, a small isolated group of some 600 Indians. … Amongst most Amazonian tribes, hallucinogenic intoxication is considered to be a collective journey into the subconscious and, as such, is a quintessentially social event. … The Waorani, however, consider the use of hallucinogens to be an aggressive anti-social act; so the shaman, or ido, who desires to project a curse takes the drug alone or accompanied only by his wife at night in the secrecy of the forest or in an isolated house. …

Of particular botanical interest is the fact that this peculiar cultural practise involves hallucinogenic plants, one rarely used and one until now unreported. The Waorani have two hallucinogens: Banisteriopsisniun muricata and an as yet undescribed basidiolichen of the genus Dictyonema.

The former is morphologically very similar to other commonly used … species such as ayahuasca, Banisieriopsis Caapi … On the other hand, no basidiolichen has yet been reported to be employed as a hallucinogen. [emphasis mine]

In that paper, Davis and Yost described the new lichen species as “extremely rare.” So rare, in fact, that Yost had “heard references to it for over seven years before encountering it in the forest.” Imagine being an explorer, dedicating your life to studying the people and plants of far-flung regions, and finally discovering an elusive psychedelic lichen you’ve been hearing about for seven years.

Even the indigenous Waorani people did not have specimens of the lichen, which they call nɇnɇndapɇ, on hand. Natives told the researchers that its last known shamanic use was “some four generations ago approximately eighty years when ‘bad shaman ate it to send a curse to cause other Waorani to die.’” Wade Davis and Jim Yost became the first known Westerners to encounter nɇnɇndapɇ, and preserved the specimen for future analysis.

Fast forward 33 years. In 2014, Michaela Schmull and her colleagues analyzed the sample’s DNA and determined that it was a new species, which they named Dictyonema huaorani. (Huaorani is an alternate spelling of Waorani, the original ‘discoverers’ of this species.) Schmull’s team examined an extract of the lichen using liquid chromatography-mass spectometry (LC-MS) techniques, and identified tryptamine, psilocybin, and 5-MeO-DMT, as well as 5-methoxytryptamine (5-MeOT), 5-MeO-NMT, and 5-methoxytryptamine (5-MT).

It is important to note that without reference compounds — in other words, available samples of the chemicals in question — these results are suggestive rather than conclusive. Since compounds like 5-MeO-DMT have never been observed in a fungus or lichen before, it’s unlikely that all of these identifications are correct.

And although fungi are well known for producing psilocybin, the family to which this fungal lichen belongs — Hygrophoraceae — has no other known psilocybin-producing species. Of all the mentioned compounds, the researchers speculate that their identification of tryptamine and psilocybin are most likely to be correct.

Lichens Are Amazing

Imagine being an explorer, dedicating your life to exploring the people and plants of far-flung regions, and finally discovering an elusive psychedelic lichen you’ve been hearing about for seven years.

Lichens are unusual and fascinating organisms — in fact, a lichen is not a single organism, but a symbiotic partnership between a fungus and an alga. The fungus provides the filamental structure that protects, hydrates, and anchors the alga; the alga photosynthesizes the sugars that both organisms require to live. Lichens are exceptionally adaptive and are found in almost every climate on earth, which cannot be said of their individual components living in isolation. The partnership benefits both parties and greatly extends the habitats where they may thrive.

The genus of Dictyonema is unusual even among lichens. In most lichens, the fungal component is an Ascomycete, but about 1% of lichens are composed of a Basidiomycete fungus instead. The algal partner varies, too — in about 10% of lichens, the photosynthesizing partner is not an alga at all, but a cyanobacterium. Members of Dictyonemaare very strange because they combine both variations, a cyanobacterium and a basidiomycete fungus, in one lichen.

Add to this the apparently psychedelic qualities of Dictyonema huaorani and you have one extremely unique species!

The researchers offer a qualification about their results:

Due to our inability to use pure reference compounds and scarce amount of sample for compound identification, however, our analyses were not able to determine conclusively the presence of hallucinogenic substances.

The scarcity of the sample can’t be helped. The unavailability of “pure reference compounds” like psilocybin, however, is an entirely artificial problem, a result of the War on Drugs which halted psychedelic research for over 40 years and continues to hinder its progress. If these substances were not made so arbitrarily difficult for researchers to obtain, we may already have a conclusive identification of the psychedelic agents present in this newly discovered species.

@ Psychedelic Research Google Community

References

Schmull, Michaela. “Dictyonema huaorani (Agaricales: Hygrophoraceae), a new lichenized basidiomycete from Amazonian Ecuador with presumed hallucinogenic properties.” The Bryologist 117(4):386-394. 2014.

UBC Botanical Garden and Centre for Plant Research

Davis, E. Wade. “The Ethnobotany of the Waorani of Eastern Ecuador.” Botanical Museum Leaflets Harvard University. Vol. 29, No. 3 (1983): 159-217.

Davis, E. Wade. “Novel Hallucinogens from Eastern Ecuador.” Botanical Museum Leaflets Harvard University. Vol. 29, No. 3 (1983): 291-95.