Since its 60s counterculture heyday, LSD has been closely associated with music. But it’s not just artistic proclivities that link them: Researchers have found that listening to music can actually affect the LSD experience on a neurological level—and they have brain scans to back it.

Mendel Kaelen, a PhD student in neuroscience at Imperial College, has led several studies investigating the combined influence of music and psychedelic drugs in human trials. One of the challenges? Choosing the music.

In recent trials, it’s been Kaelen’s responsibility (among other things) to design the perfect playlist for a scientifically-sanctioned psychedelic trip with strict research requirements—a task that requires both a creative sensibility and a respect for the rigorous framework of scientific procedures.

He explained that the need to include music in these trials is borne directly from the rising interest in studying psychedelic drugs and considering how they could be used therapeutically: One of the main purposes of the Imperial College team’s research with these substances is to explore how they might be used to help treat mental illnesses such as depression.

The idea of incorporating music into psychedelic therapy isn’t new; it was a point of great interest to music therapists in the 60s. But Kaelen is trying to ground it in a solid scientific framework. “If you look at these clinical trials right now, all of them, without any exception, use music as part of the therapy model,” he said in a phone interview. “If music plays such an important role in the therapeutic method, we need to ask a lot of important scientific questions related to that in order to really move the field forward—to really make sure that we have an empirical understanding of the role of music within therapeutic work.”

I spoke to Kaelen about his research into the effects of music on the psychedelic experience (and vice versa), how this could inform the therapeutic use of these drugs, and, most importantly, how the hell he selects the music for such unusual situations.

Before we can imagine therapists giving patients some LSD and a pair of headphones, it’s important to establish a few basic facts about the combined effects of music and psychedelics. In a pilot study published last year in the journal Psychopharmacology, Kaelen and his fellow researchers went back to basics and tested a simple hypothesis inspired by psychotherapy in the 50s and 60s: Do psychedelics enhance the emotional response to music?

In the study, ten volunteers listened to five instrumental tracks on two occasions. On the first, they were given a placebo; on the second, they were given LSD.

What music is suitable for judging emotional responses on acid? The participants listened to two different playlists, the “emotional potency” of which were balanced based on earlier assessments from a separate group of people. The selected tracks were among those judged most likeable and least familiar—Kaelen explained that familiarity with a track could influence people’s emotional response. “If music is too familiar, it can reduce the ability to have a new experience, because you already had an experience with that song before in your life,” he noted.

The resulting playlists both include ambient and neo-classical tracks by artists Brian McBride, Ólafur Arnalds, Arve Henriksen, and Greg Haines. Kaelen said Haines, a British composer, was a popular choice—he’s used tracks by him in several trials. “His song was just pointed out again and again as a favourite, so to speak,” he said.

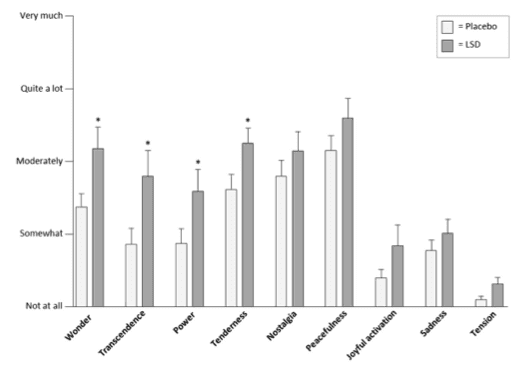

The participants in the emotional response study were asked to rate how emotionally affected they were by the music on a scale of 1-100 and to complete a questionnaire known as the GEMS-9, which asked them to give a rating for different kinds of emotional responses to the music, such as peacefulness or tension. The researchers found that participants reported a significantly higher emotional response to the music when they took LSD, and that emotions related to “wonder,” “transcendence,” “tenderness,” and “power” were particularly increased.

They conclude that their finding “reinforces a long-held assumption that music takes on an intensified quality and significance under the influence of psychedelic drugs,” and that this could be useful for therapeutic applications. They add that feelings of transcendence and wonder are often considered to contribute to “spiritual-type” experiences and that, therefore, the combination of music and LSD may bring on this kind of trip.

The subjective experience of participants is one thing, but Kaelen and his colleagues have also used neuroimaging studies to explore the relationship between music and LSD in the brain.

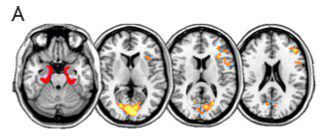

Following the pilot study, Kaelen was involved in a groundbreaking trial that used fMRI and MEG scans to image the brain on LSD for the first time. Twenty volunteers were injected with 75 micrograms of LSD (and, on a separate occasion, a placebo) and had their brains imaged. The research provided insights into the visual hallucinations and changes in consciousness associated with psychedelic trips.

During this same trial, participants had periods of silence and periods of listening to music while they were in the fMRI scanner, and then answered questions about their mood and any imagery they experienced (they had their eyes closed). The researchers discovered a link between music and the kind of visuals people saw when on LSD.

The study, published in European Neuropsychopharmacology, found that information flow between the parahippocampal cortex—which has been linked to memory—and the visual cortex was reduced under LSD. But with music as well, communication between these two areas increased.

Importantly, the magnitude of this effect correlated with people reporting more complex visions and particularly images that were autobiographical in nature.

“Very often, people have vivid, eyes-closed imagery, where they are interacting—it’s not like they’re looking at a screen where they see certain images that are entertaining; there’s a personal interaction with that imagery,” said Kaelen.

The personal nature of the psychedelic experience makes it tough to pick a soundtrack. “That was a very challenging thing actually, because we all have different musical preferences of course,” said Kaelen. They couldn’t allow people to bring their own music as they needed to standardize practices in order to get clean scientific data.

Kaelen started by selecting a library of music which was then put to a separate group to be rated on their emotional impact. “Initially I wanted to work with very evocative, very emotionally strong neo-classical music, but considering the challenging environment people are in within the fMRI scanner, I actually thought maybe it wouldn’t be a good idea to expose people to really intense emotional environment,” he explained. “I ended up selecting music that has a very relaxing and very positive general atmosphere within it—mainly music by an ambient music artist called Robert Rich.”

Kaelen eventually selected two seven-minute excerpts from tracks by Robert Rich and Lisa Moskow, from their collaborative 1995 album Yearning. He described the tracks as calming with melodic strings (Moskow plays a sarod, an Indian instrument similar to a sitar). “It had a lot of very typical ambient instruments in there—a synth, a flute—but it also had an instrument with a clear melody line that people could follow,” he said.

Kaelen said Rich’s work was actually one of the reasons he was attracted to exploring the effects of music in his research. “Robert Rich is amazing, because he really started to make music on the understanding that music can be a really potent way to induce and also guide altered states,” he said, referring to the musician’s 80s “sleep concerts” where he would play for a dozing audience.

Playing music in an MRI scanner offers its own challenges, even if your subjects aren’t on LSD. The researchers used special MRI-compatible headphones (which don’t contain a magnetic coil) to try to keep decent sound quality over the whirr of the machine. While a couple people didn’t like the music, Kaelen said most welcomed it as a “warmer” alternative to the scanner noise.

While these studies have shed light on the effects of music and LSD when experienced in combination, a driving force of the Imperial College team’s research is to explore how psychedelics could be used in a therapeutic context. Research has shown that, used under the guidance of a therapist, these drugs could be useful in treating illnesses such as depression, anxiety, and addiction. Kaelen is interested in how music can help.

The basic idea has its roots in psychedelic therapy in the 60s, before these drugs became illegal and therefore harder to work with.

“People started to realize that it’s not the drug itself that provides a therapeutic effect; it’s the experience that the drug is able to produce in interaction with the therapist, with the environment, that has that potential,” explained Kaelen. “Out of this realization, people basically started to experiment with different ways of how to design the experience; how to make sure that people have an experience that is indeed therapeutic.”

Music was soon recognized as a way to try to help provide some structure to the experience.

Recently, Kaelen was involved in a clinical trial that involved giving psilocybin—the psychedelic compound in “magic mushrooms”—to patients with treatment-resistant depression. (The results have not yet been published.) The trial took place in a hospital room decorated to look less clinical and scary—Kaelen noted that the sterile hospital room was probably “one of the worst places to take a psychedelic drug.”

Putting together a playlist for this trial was much more challenging, as it needed to soundtrack the therapeutic environment for around six hours, as opposed to the few minutes in the brain imaging study. Patients could either listen through the sound system in the room or through earbuds, but the music was always on.

Kaelen said his playlist was partly inspired by the work of previous researchers such as music therapist Helen Bonny, who developed a method called Guided Imagery and Music in the 60s to help explore states of consciousness in a therapeutic context.

He designed his playlist to reflect the changing experience of the drug, from the onset of the psilocybin effects building up to the peak of the experience and then the comedown. “For all these different phases within the playlist, different needs are there to be met that the music can help with,” said Kaelen.

For example, many people are naturally nervous before the drug takes effect, so Kaelen selected music that might be calming and reassuring. During the onset, the music becomes more rhythmic, and during the peak of the drug’s effect, which lasts a couple of hours, the music swings between different emotional intensities in what Kaelen called a pendulum effect.

“It wouldn’t be good for people to be constantly exposed to really emotional music; there needs to be a moment where the individual is able to reflect on that experience as well,” he explained.

Kaelen said it took him months to select and mix tracks for the trial, which he took from his own library as well as recommendations in Bonny’s work. He stayed away from the more classical or Christian tracks, as he said it was important to him that the music reflected the times and didn’t have connotations to any specific religion. Kaelen makes his own experimental electronic music, so was able to mix the tracks himself and adapt the spacing and volume to suit the experience he wanted to choreograph.

He could not share his full playlist for the study as he may use it in other studies, and can’t risk people becoming too familiar with the exact music. However, he shared some tracks: Brian Eno and Harold Budd’s “Against the Sky” features in the onset phase as a calming track; contemporary classical musician Henryk Górecki’s “Sostenuto tranquillo ma cantabile” plays in the lead-up to the peak and is, according to Kaelen, the first “emotionally evocative” piece; and Greg Haines makes an appearance with “183 Times”—a song also used in the pilot study exploring emotional enhancement—during the peak phase.

To demonstrate the effect of the music, Kaelen shared with me some patient experiences. In response to “183 Times,” one patient said it was “The peak of the experience, the track that seemed to sum up the whole experience. Moved beyond words, it accompanied the strongest part of the inner journey. Mind blowing.”

Another shared, “This song made me cry a lot. It was very sad and beautiful, crying during this song felt like emotional release, release of sadness and bad feelings towards myself. It made me think of struggles I had to go through life being depressed. At the end of this song I felt cleansed and better and I felt compassion towards myself.”

Ultimately, Kaelen said, some people connected really well with the music, and others didn’t.

“The selection of songs was actually incredibly difficult, because every single song I considered, I asked myself the question, ‘Do I think this song works for the patient because it works for me, or does the song work for the patient because I think it carries with it a message that is universal, that is intrinsic to the music itself?’” Kaelen said.

There’s not really a science to it—at least not yet.

“To be honest with you, when I started doing it, I also felt the huge responsibility that designing a music playlist like this brings, because people will be influenced by it incredibly,” he admitted.

One major thing Kaelen took from the trial was that, while he still believes there is some universality to music, it’s impossible to make a standardized playlist suitable for everyone. He suggests that in the future, a therapist should have some way of adapting the music to their individual patients’ needs. Moving forward, that’s something he’s working on.

He emphasized that the most important aspect of using psychedelics therapeutically was having a strong rapport between patient and therapist.

“The music is, in essence, always and only there to be in service of the central therapeutic process; that is to support the highly personal eyes-closed journey that is unfolding over the hours,” he said.