Most anyone with a decent interest in psychedelics knows of the late Terence McKenna, the famous American philosopher and “mushroom guru.” Fewer people are aware that his brother Dennis McKenna is still alive and kicking.

The other McKenna is an ethnopharmacologist, research pharmacognosist, lecturer, author, proponent of responsible psychedelic therapy, and someone who wants to help you and I to heal and liberate our minds and hearts.

A couple days ago, I happened upon an extraordinary clip of Dennis discussing depression medications on the Joe Rogan Experience Podcast.

In just 3 minutes, Dennis argues that today’s most common antidepressant medications—selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)—are a kind of “Band-Aid solution.” He describes how psychedelics (or, “ecodelics“) can be used as an alternative treatmentfor depression and discusses why the pharmaceutical industry may not want psychedelic medicines to become a viable option for people suffering from conditions currently treated with SSRIs.

Take 3 minutes to watch this wonderful clip, or scroll below to read the major insights.

Can Psychedelics Treat Depression?

It seems that Dennis takes after his brother, in the sense that he is able to distill a tremendous amount of perspective into a relatively short amount of speech.

The clip begins with McKenna discussing the virtues of SSRIs versus those of psychedelics:

“Antidepressants are overprescribed and overused for too many things. They don’t really help people get to the root of their problems. They just kind of Band-Aid it over, and you feel sort of normal, and you can be a productive citizen, and you don’t really think about things too much. They’re prescribed for PTSD, you know, but they don’t cure PTSD—they just kind of dampen it down and bury it. They don’t give you an opportunity to really look at issues and work them through. This is why psychedelics are not a good model for Big Pharma. Big Pharma wants things like SSRIs, which you take every day for the rest of your life. That’s the business model. Psychedelics are things that you might take a few times and work through your issues, and you don’t need antidepressants after that. I’ve talked to many, many people who had been on antidepressants. They go to South America. They take a few ayahuasca sessions. They never have to go back to antidepressants. Again, they can get off it for good. Many people have that experience.”

We should note that McKenna is not suggesting that long-term medications are inherently “bad” or that there isn’t a place for SSRIs as a treatment for depression and other conditions. Rather, he’s suggesting that these medications are overprescribed, and that psychedelic therapy presents a promising alternative.

It might seem too good to be true to think that a few sessions of psychedelic therapy with psilocybin or ayahuasca could permanently alleviate chronic depression, yet evidence suggests that this is true. Innumerable personal anecdotes (like this one on ayahuasca saving a life or this one on psilocybin curing depression) suggest that psychedelics have the potential to catalyze “breakthroughs.” A breakthrough is an experience in which subjects see and understand their lives and minds in entirely new ways, gaining a renewed sense of the value of life and constructive insight into their peculiar psychic baggage.

Psychedelics often confront people with their core issues and fears—dark areas of the mind that are otherwise unconscious and inaccessible. This is why—as any experienced user of psychedelics will tell you—psychedelics can sometimes cause grim and terrifying experiences. In a great essay on psychedelics, author Sam Harris wrote of an LSD trip gone awry in Nepal:

For the next several hours my mind became a perfect instrument of self-torture. All that remained was a continuous shattering and terror for which I have no words.

Still, many experienced users report that their worst trips ended up being the most useful and healing over time. This is because bad trips tend to result from being forced to confront deep fears, taboos, and unresolved issues in one’s unconscious mind. This can be a harrowing experience, but it is through encountering one’s deepest fears and baggage that one is given the chance to see those issues in a new light, to accept them deeply, to re-frame unconscious assumptions about life, and to reintegrate repressed aspects of consciousness.

Clinical research into psychedelics became professionally marginalized in the 1960s and virtually dropped off entirely after psilocybin, LSD, and other psychedelics were outlawed by Nixon’s Controlled Substances Act of 1970, which classified these compounds as having “no recognized medicinal value.” This claim was contradicted by numerous studies conducted in multiple countries in the 50s and 60s that had suggested significant potential for psychedelics to aid in the treatment of alcoholism and addiction, serve as a tool for psychotherapy, and help terminally ill patients to cope with despair.

Some have argued that governments are so hostile toward psychedelics because they empower individuals, thereby posing a threat to existing structures of authority and control. As Dr. Roland Griffiths, a psychopharmacologist at Johns Hopkins University put it:

There is such a sense of authority that comes out of the primary mystical experience that it can be threatening to existing hierarchical structures. We ended up demonizing these compounds. Can you think of another area of science regarded as so dangerous and taboo that all research gets shut down for decades? It’s unprecedented in modern science.”

Today, we’re experiencing a resurgence in interest in the beneficial properties of psychedelics. Within the last decade medical research into psychedelic therapy has resumed and is beginning to gain momentum. 2006 was a milestone year in which the journal Psychopharmacology published alandmark article by researchers at Johns Hopkins University titled “Psilocybin Can Occasion Mystical-Type Experiences Having Substantial and Sustained Personal Meaning and Spiritual Significance.”

In the study, 30 people who had never used psychedelics were given two to three sessions with psilocybin at 2-month intervals. The study found that the participants—everyday citizens who could’ve easily been your family members—“rated the psilocybin experience as having substantial personal meaning and spiritual significance and attributed to the experience sustained positive changes in attitudes and behavior consistent with changes rated by community observers.”

With this 2006 study at Johns Hopkins, scientists at one of the world’s most reputable academic institutions had cast a vote in favor of psychedelic research. Beyond that, they had reached conclusions suggesting that psychedelics could be efficacious in nourishing subjective mental well-being. Though there remain significant barriers to psychedelic research, this study was a kind of clarion call to other institutions to contribute to a new wave of exciting research. Dr. Anthony Bossis, a psychologist and researcher at New York University, said the following of the study:

“It solidified our confidence that we could do this work. Johns Hopkins had shown it could be done safely. . . . The fact that psychedelic research was being done at Hopkins—considered the premier medical center in the country—made it easier to get it approved [at N.Y.U.]. It was an amazing study, with such an elegant design. And it opened up the field.”

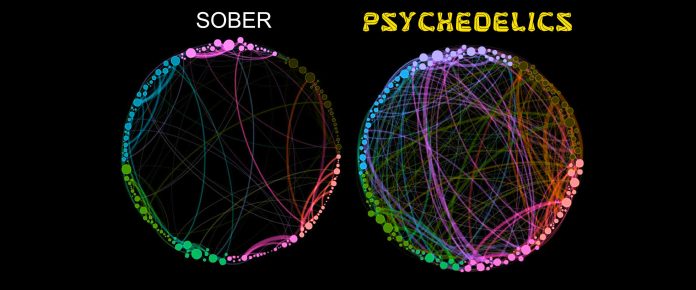

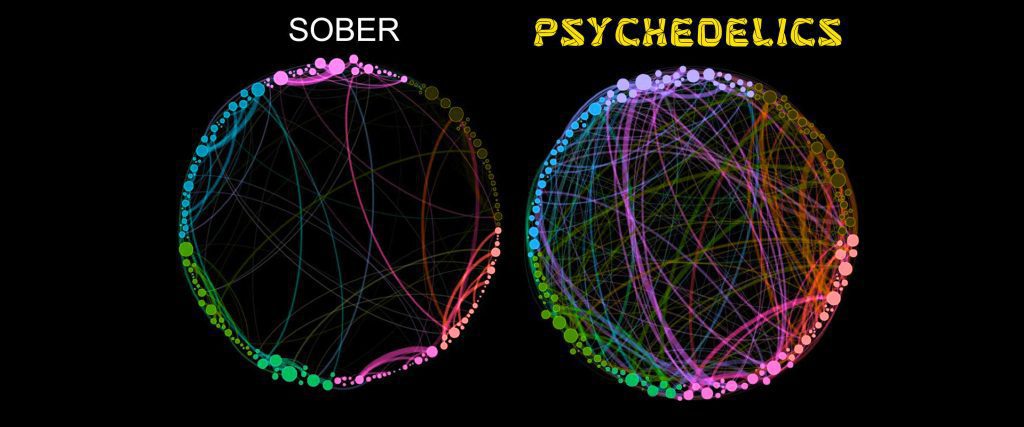

Since then, numerous other studies have been conducted connecting psychedelic therapy with increases in subjective well-being. A 2014 study published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface “compared M.R.I.s of the brains of subjects injected with psilocybin with scans of their normal brain activity,” according to a NY Times op-ed. “The brains on psilocybin showed radically different connectivity patterns between cortical regions (the parts thought to play an important role in consciousness).” The author of the op-ed explained that,

“The fact that under the influence of psilocybin the brain temporarily behaves in a new way may be medically significant in treating psychological disorders like depression. ‘When suffering depression, people get stuck in a spiral of negative thoughts and cannot get out of it,’ Dr. [Paul] Expert said. ‘One can imagine that breaking any pattern that prevents a “proper” functioning of the brain can be helpful.’ Think of it as tripping a breaker or rebooting your computer.”

Dr. David Nutt, a British psychiatrist and neuropsychopharmacologist who is one of the leading researchers in these groundbreaking brain-imaging studies, said this of the studies in a recent interview:

“We’ve [discovered] that these drugs have quite profound effects, for instance, they switch off the part of the brain that causes depression. Now we’re doing a trial using psilocybin to treat depression because we think where conventional treatments fail, psilocybin might work.”

So according to these recent studies, psychedelics actually temporarily “switch off” the part of the brain that causes depression. Beyond that, they radically shift connectivity in the brain, allowing interaction between parts of the brain that typically remain isolated. This observed shift in connectivity begins to suggest why psychedelics give people access to otherwise-unconscious areas of their psyche and contain such astounding transformative potential.

Barriers to Psychedelics as Medicine

As you can see, Dennis McKenna’s assertions about the therapeutic potential of psychedelics are more than one man’s opinions. Paradigm-breaking studies in psychology and neuroscience, anthropological findings, results from therapeutic tests, and thousands of personal anecdotes suggest that psychedelics are viable medicines for many illnesses, some of which have no other known cures/treatments.

It seems that the cultural tides are shifting in terms of our acceptance of psychedelics, but it remains to be seen whether these powerful tools for psychotherapy will become accessible to the masses.

Legal Barriers

The Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) is currently conducting phase III of trial testing of MDMA as a treatment for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and hopes to offer therapy to the general public by 2022. However, the road to MAPS’ success with these MDMA trials has been a long one, spanning over a decade. This is due, in part, to the stringent legal regulations on psychedelic research in the US, UK, and other countries. These regulations make it much more difficult to conduct studies on psychedelic compounds as compared to other drugs and threaten the potential for wide access to psychedelic medicines.

Dr. David Nutt, whom I mentioned earlier, has spoken against the legal restrictions that have severely limited the advancement of his team’s auspicious research. In a recent interview, Dr. Nutt called psychedelic prohibition the “worst censorship of medicine and clinical research in the history of the world.” Of his own studies, he said,

“The depression trial took three years to work through all the different regulations. We spent almost all the money we had just getting the drug and getting through those regulations. . . . The world needs to wake up to the potential of drugs like LSD and psilocybin, and also cannabis. These drugs have enormous potential. Every day that goes on with these drugs illegal, patients are suffering; patients are committing suicide because they are not getting treated for their depressions or their pain. So, it is a priority for medicine in the world to reverse these laws.”

The Pharmaceutical Industry

Another barrier to the ecodelic experience becoming widely accessible may reside in the nature of the pharmaceutical industry. As Dennis McKenna explains,

“… Big Pharma wants drugs that people consume… You can’t use [psychedelics]… in a therapeutic session without intense psychotherapy, whether that’s actual psychotherapy or shamanism or some combination of those things. These are drugs that have to be used in context. The ‘take two and call me in the morning’ model doesn’t work for these. These have to be used in a very highly controlled set and setting. So I think where the business model comes in is you have places where people can go and get this kind of therapy… Our whole bio-medical-industrial complex is set up to encourage Band-Aid solutions. You have a problem. You go see your psychiatrist. He has seven minutes, if he’s lucky, to talk to you. Here’s a prescription. Get out of here. That’s the way it works. With psychedelics, you actually have to have a therapist who will sit down and talk with you. This is a whole novel concept. So I think where the business potential comes in is to have centers of therapy where you can go and get psychedelic therapy. And the emphasis is more on the setting and the services provided than on the actual chemicals.”

McKenna is in favor of psychedelic medicines becoming accessible in a clinical setting. Some onlookers have pointed out that the medicalization of psychedelics would still limit access to psychedelics to those who are “sick” and are approved by doctors. This would prevent the use of psychedelics for what some have called “the betterment of well people.” This term is meant to refer to the entheogenic potential of psychedelic medicines to trigger spiritual or mystical experiences—experiences that can have profoundly life-affirming, transformative effects on people who are not “sick” in any clinical sense.

So we should be careful to note that the availability of psychedelics in a clinical setting would not equate to the full cognitive liberty to experiment with one’s consciousness. Still, MAPS and similar organizations argue that medical availability is a step in the right direction and might open doors to a future in which individuals can procure a license to use psychedelics as they please.

But as McKenna points out, even wide clinical availability may be difficult to attain, given the aforementioned legal restrictions and the fact that the pharmaceutical industry is comprised ofprivate companies. There are undoubtedly many people working in these companies that care about advancing medicine and improving our collective health. However, one should not overlook that these are businesses we’re talking about, and that the top priority of any business must be its ability to profit.

McKenna notes that it’s good for business if people are forced to go on buying and consuming pills for the entirety of their lives. Psychedelics might actually offer people a permanent solution to certain mental disorders by addressing their root causes, but curing people in a few months and sending them on their way would likely be far less profitable than finding recurring customers.

McKenna presciently points out, though, that there is a potentially lucrative business model that will likely become the norm for psychedelics. Psychedelics require a specific sort of physical and mental environment, or “set and setting,” to be effective. Providing this context and the professional facilitators necessary to ensure constructive therapy will doubtlessly be somewhat expensive, and so companies will be able to turn a profit by charging people for the professional help and facilities necessary for effective therapy.

Hope

The hope, of course, is that the costs will be sufficiently low—or will eventually be subsidized for those who cannot afford the price tag—to allow anyone and everyone who might benefit greatly from psychedelic medicines to pursue healing in a clinical setting.

That is a world I—and many of you, I’m sure—would like to see: a world in which we utilize these powerful tools to promote healing and well-being in a modern civilization that leaves many feeling alienated and helpless.

If psychedelic therapy becomes mainstream, we will have witnessed a tremendous shift in the direction of fuller cognitive liberty and wider exploration of human potential.

Beyond that, we will be one step closer harnessing the wisdom contained in the more mystical aspects of the ecodelic experience to re-imagine our global systems and bring about a more equitable, sustainable human enterprise.

A Final Note on Safety

As we repeatedly stress on HighExistence, psychedelicsmust be approached with reverence and caution. We believe that in a loving context, psychedelics are powerful medicines with tremendous potential, but there are a number of physical and psychological safety concerns that one should consider before journeying with psychedelics. Please, please do plenty of research, and do not take psychedelics if you have reason to believe that they will not jibe with your personality or particular mental baggage. The Essential Psychedelic Guide on Erowid is an exceptional free resource, and we recommend reading it, especially the section on ‘Psychedelic Safety,’ before ever dabbling in these substances. You should understand the risks, understand your reasons for experimenting and the benefits you hope to gain, and use the substances responsibly. Take care, and happy tripping. : )

Further Study:

If you would like to learn more about the healing potential of psychedelic medicines, we at High Existence recommend Acid Test: LSD, Ecstasy, and the Power to Heal by Tom Shroder. Acid Test is the true story of what really happened when the DEA banned psychedelics for personal use, therapeutic applications, and even scientific research. Shroder explains how a group of psychedelic geniuses tried to prevent this, failed, and then decided to beat the system from the inside out. It’s basically the story of the origins of MDMA, its use in therapy, the DEA ban, and the founding of MAPS and their decision to do research on PTSD with veterans.

It’s told through the genealogical stories of Michael Mithoefer, a psychedelic therapist, Nicholas Blackstone, an Iraq vet with PTSD who participated in a MAPS study and has had significantly less symptoms than with any other therapy he had tried, and Rick Doblin, the founder of MAPS. It’s an illuminating, well-researched, accessible introduction to psychedelic medicines.

Helping the Movement:

You can help this movement by spreading non-dogmatic perspectives on psychedelics—i.e. personal anecdotes, scientific research, anthropological findings, etc. You might even share this very article. 🙂