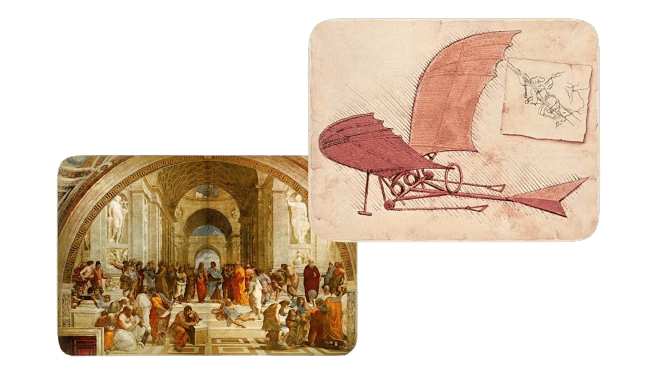

When we hear the term Renaissance Art, what normally comes to mind are iconic works like Leonardo da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa”, Michelangelo’s “David”, and Raphael’s “School of Athens”. But you would be forgiven for forgetting that pieces like the following are also associated with the explosion of art that emerged from this period in history.

The issue with pieces such as this is that, in a period often regarded as a revisioning of the world, where artists endeavored to draw and paint things as they really were, paintings such as this make no sense.

So, what could have caused reputable artists of this time to depict the world in this way? And could it have something to do with the third-century desert father, a psychedelic fungal plague, and a little dose of a warped but yet still clear-sighted perspective of the world all around us?

The Renaissance period is often regarded as one of the most influential turning points in recent history. It is remarked as the period that transformed society from darkness to light, with many reputable artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael peddling the movement with phenomenal artwork and technologies.

But amongst the great works of this time, there exist some pieces that were made memorable not particularly for their finesse of stroke, but rather because of how plain strange they were. Such as this piece, titled “The Temptation of Saint Anthony”, created by Hieronymus Bosch circa 1550, replete with all the peculiarities on display, such as flying fish-wolf, homicidal egg with legs, and even Cubone now armed with a machete instead of his signature bone club.

The same question comes to many a mind: where on God’s Green Earth did Bosch source his creative insanity from? Could his artwork hint at other, stranger factors influencing this time?

Questions to which Bosch scholar, Lorinda S. Dixon, would offer one word: ergotism. The psychedelic fungal plague which infected much of Northern Europe at the time was known to cause vivid hallucinations to those infected, 16th-century peasants and artists alike.

With many clues and connections linking this theory together. For instance, at the time, ergotism was better known as St. Anthony’s Fire, related to the title of Bosch’s work, The Temptation of St. Anthony.

As well as the saint himself who wandered the Egyptian desert during the 3rd century.An ancient tale often read as hallucinatory with a blend of imagery, ecstasy, and madness. And a story from which Bosch took much of his inspiration, with the saint being depicted in his work over 20 times.

But his inspiration didn’t stop there. By the time of his death in 1516, Bosch would have experienced ergot outbreaks himself, with knowledge of up to 40 fungal plagues since the 9th century.

Evidence of these outbreaks is found throughout his artwork. Such as characters, high in the sky, believing they can fly, a common misconception associated with ergot poisoning, wide-eyed magi, pupils less than shy, handing out a curious concoction to any guy.

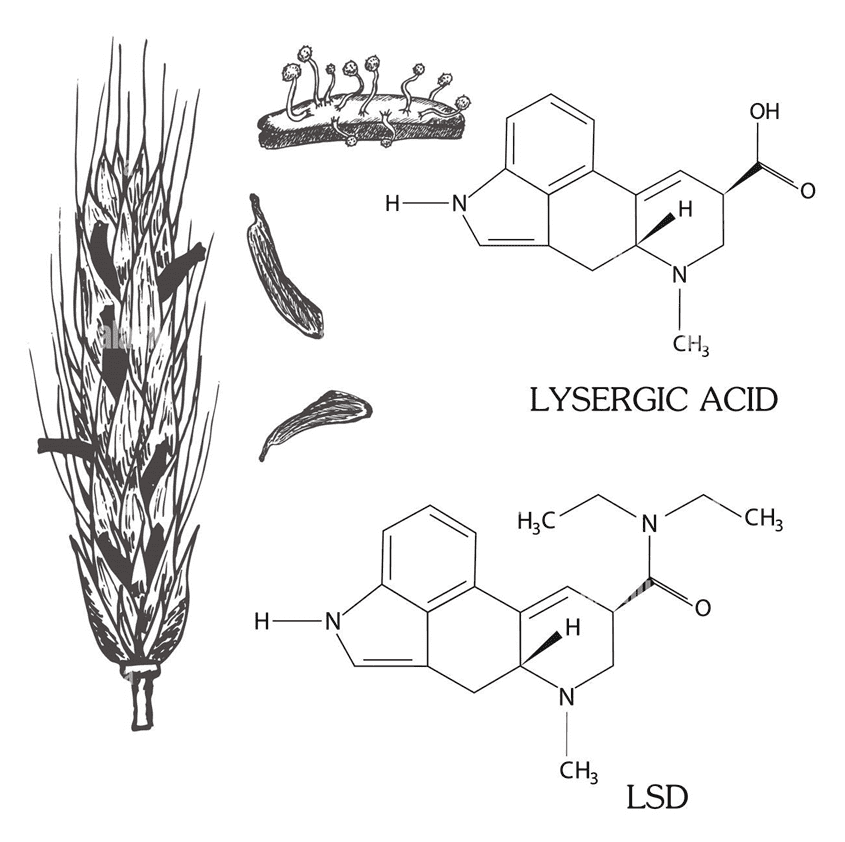

As well as the pièce de résistance, a shoot of rye, bursting high, ridden with sclerotium, as black as the night sky – a telltale sign of ergot poisoning, which none can deny. The black nodules are known to contain lysergic acid, the natural precursor to LSD-25, and a compound which produces different but still comparable effects.

All evidence points in one direction, posing the question: maybe one of the most famed artists of the Renaissance wasn’t of unsound mind or eye, but instead, just really, really high.