Ketamine or “K” is a dissociative anaesthetic drug used in a variety of clinical settings, from veterinary clinics to the battlefield and hospital emergency rooms. It is on the World Health Organization’s Essential drug list and highly safe for clinical use because it anaesthetizes patients without threatening their airways and other vital nervous system functions, and it is even used regularly on children.

K is also widely used recreationally for its psychedelic effects at sub-anaesthetic or even fully anaesthetic doses. The latter is often called a “K-hole”, the peak psychedelic experience of a ketamine trip. There are many interesting concepts surrounding the experiential topography of K, which I will not be discussing here. There is also an addictive potential for ketamine in its recreational use, but less than other substances such as nicotine, cocaine, opiates, and alcohol.

K has found other uses over the last fifty years, such as a potential treatment of chronic pain disorders and what this article intends to demystify, is its use as a fast acting anti-depressant.

Ketamine For Depression

The potential of these anti-depressant effects are remarkable; a single session with K can help reduce symptoms in treatment-resistant depression, bipolar disorder, and acute suicidality for up to a week. It has also been shown to offer noticeable reduction in symptoms of both obsessive-compulsive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder. What is most interesting is that these effects come on within about two hours of onset and depending on dose and duration of administration, can last for up to a week, long after the drug has be metabolized and removed from the system. Whereas our other medications for treating depression—assuming it can be chemically treated at all—take several weeks of regular use to take effect, such is the case with Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors or SSRIs.

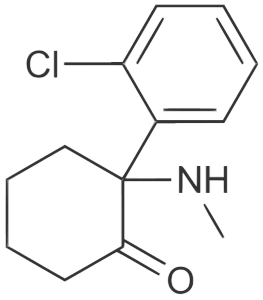

The basic action of ketamine’s immediate effect is on the glutamate neurotransmitter system, wherein it binds to a very specific dock on the NMDA receptors (this dock also binds PCP), blocking the uptake of glutamate. In that way, its actions are similar to Magnesium, leading to insight about magnesium deficiency and supplementation in the management of depression. Glutamate is the major excitatory transmitter in the brain and thus effectively cuts off “go” signals between the brain and the body (anaesthetic). Yet it also has both positive and negative effects on other neurotransmitter systems such as dopamine, acetylcholine, and the opioid system, contributing to its psychoactive effect beyond sedation.

K’s delayed effects are what seem to be playing a role in its anti-depressive actions. Ketamine seems to increase production of Brain Derived Neurotropic Factor (BDNF), and the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) in the hippocampus and the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC).

BDNF is a brain protein that helps with the production of new and protection of old neurons and synapses as well as adaptability to mood and emotions. mTOR is also a protein responsible for various functions relating to cell growth and survival. The hippocampus is a part in the brain involved in learning and memory. The mPFC is thought to be an area responsible for planning complex cognitive behaviors, such as working towards goals and determining ‘good and bad’. What is interesting here is that long-term depression actually reduces BDNF and mTOR in the hippocampus and mPFC. It also causes changes to those areas in the brain, specifically decreased neural connectivity.

A long-term effect of taking SSRIs is an increase in BDNF. This observation along with the neurophysiological pathology of depression and the effects of ketamine lead to conjecture that drugs like SSRIs actually work to improve depressive symptoms via their direct effect on serotonin, by their ability to mitigate stress while the brain increases BDNF and mTOR again, or by directly increasing BDNF themselves.

Ketamine Vs. Psilocybin

There is some interesting overlap in the potential use of psilocybin to treat depression. In humans, psilocybin has been shown to increase functional connectivity and reduce blood flow to the mPFC (giving it a break from rumination, in my opinion), as well as encourage neurogenesis in the hippocampus of mice. Yet the positive effects psilocybin has on a person seem to be long lasting. Lifetime psilocybin use has even been associated to a significantly lower rate of mental health illness compared to the general population.

In my opinion, these positive effects K has on the hippocampus and mPFC allow for thought patterns and behaviors that transcend the previously ingrained detrimental behaviors of depression. The temporary release from depressive symptoms and behaviors, in addition to an increase in the aforementioned brain proteins, as well as the modulation of dopamine, acetylcholine, and norepinephrine associated with the drug’s effect, creates a cascade of positive feeling and self-image alterations in the individual, and perhaps a celebratory sense of being free of their depression. This same cascade begins to reverse when the depressive feelings return as a result of the continuation of the same stresses having produced the depression in the first place.

I believe this happens because the temporary relief comes so fast and without any actual awareness or connection to the emotional source of the depression, that the Ketamine acts like a quick fix, rather than a rebuild. In comparison, psilocybin produces an extended positive effect on personality because the very nature of psilocybin is to face the emotional source of detrimental behavior and properly integrate into our sense of self, which includes a sense of openness, possibility, and positive mystery. In my opinion, when the root of depression is not addressed, it will eventually return when the chemical crutches are removed.

That being said, ketamine’s potential for operating as an acute antidepressant is groundbreaking and exciting. Where it fails and will continue to fail is due to an exclusively neurochemical-centric model for treating depression, rather than a psychoneuroimmunological model.

Ketamine Risks & Gains

Of course, Ketamine is also dangerous. If you are reading this as part of an intention to help yourself or someone else out of depression, there are damaging consequences to be considered. For example, regular, long-term ketamine use is associated with severe damage to the bladder, which can include the need for it to be surgical removed. It has also been shown to produce “persistent or recurrent schizotypical behaviour and memory defects”. It also has potential for addiction.

Even with K’s positive effects on things like BDNF, it also creates oxidative stress on the brain by decreasing levels of Superoxide Dismutase4, an essential antioxidant. So the more you take ketamine, the more the collateral oxidation will further stress your brain and your depressive symptoms. This is where I believe the neurological side of Ketamine dependence emerges. Psychologically, you take it, you feel good and free, for a while. Then, things turn back and you reach to the Ketamine again. Physically, each time you take it, you need an increased dose due to tolerance, which creates ever-stronger recoil of oxidation, thus a stronger desire to redose. So self-treatment with ketamine is NOT to be considered a safe alternative for those of us who have been conditioned to distrust SSRIs due to the distasteful ethics of the pharmaceutical industry.

In summary, Ketamine presents a vital opportunity to emergency medicine for the acute treatment of depression and suicidality. But in the author’s opinion, as an essential means for treating depression over the long term or accomplishing complete remission, it falls short due to its inability to physically or psychologically (or spiritually) address the root cause of depression.

Original Article appears on jameswjesso.com

Sources:

{Please note, the author is not a doctor or a certified scientist, just a well-read guy with a deep fascination for psychopharmacology. Statements directly cited are the information of others; anything else is the personal opinion of the author. Citations are presented accurately, but casually, for reference to the sources of facts presented in this article, but are not to be considered a complete or exhausted list of relevant information}

1 – ‘New Mechanisms Elicited with Ketamine in Treatment-Resistant Depression’ Ronald S. Duman, PhD, 2012, (Lecture), YalePsychiatry/YouTube

2 – ‘Ketamine: clinical significance & recreational harm reduction’ Ian Mitchell, 2015, (Podcast Interview), ATTMind Radio

Ketamine: Clinical Significance & Recreational Harm Reduction w/ Ian Mitchell ~ Ep. 15

3 – ‘Ketamine – more mechanisms of action than just nmda blockade’ Jamie Sleigh et al., 2014, (Article In Digital Journal), Trends In Anaesthesia & Critical Care

http://www.trendsanaesthesiacriticalcare.com/article/S2210-8440(14)20006-2/fulltext

4 – ‘Antidepressant Mechanism Of Ketamine: Perspective From Preclinical Studies’ Lisa Scheuing et al., 2015, (Article In Digital Journal), Frontiers In Nueroscience

http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fnins.2015.00249/full

5 – ‘Ketamine for chronic pain: risks and benefits’ Marieke Niesters et al., 2014, (Article in Journal), British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology [Volume 77, Issue 2, pages 357–367]

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bcp.12094/full

6 – ‘Prefrontal cortex’, (Website), Wikipedia, accessed Dec. 28, 2015

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prefrontal_cortex

7 – ‘Hippocampus’, (Website), Wikipedia, accessed Dec. 28, 2015

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hippocampus

8 – ‘Mechanistic target of rapamycin’, (Website), Wikipedia, accessed Dec. 28, 2015

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mechanistic_target_of_rapamycin

9 – ‘Brain-derived neurotrophic factor’ Wikipedia, (Website), accessed Dec. 28, 2015

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brain-derived_neurotrophic_factor

10 – ‘Magnesium and the Ketamine Connection’ Emily Deans, (Website Article), Psychology Today, accessed Dec. 28, 2015

https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/evolutionary-psychiatry/201410/magnesium-and-the-ketamine-connection

11 – ‘Neural correlates of the psychedelic state as determined by fMRI studies with psilocybin’ Robin L. Carhart-Harris et al., (Article In Digital Journal), 2012, PNAS

http://www.pnas.org/content/109/6/2138.full

12 – ‘Mystical Experiences Occasioned by the Hallucinogen Psilocybin Lead to Increases in the Personality Domain of Openness’ Katherine L. MacLean et al., (Article In Digital Journal), 2011, Journal Of Psychopharmacology

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3537171/

13 – ‘Effects of psilocybin on hippocampal neurogenesis and extinction of trace fear conditioning’ Briony J Catlow et al., (Article In Journal), 2013, Experimental Brain Research [Volume 228, Issue 4, pp 481-491]

http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00221-013-3579-0

14 – ‘Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance’ Roland R. Griffiths et al., (Article in Journal), 2006, Psychopharmacology [Volume 187, Issue 3, pp 268-283]

http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00213-006-0457-5

15 – ‘Homological scaffolds of brain functional networks’ Giovanni Petri et al., (Article In Digital Journal), 2014, Journal of The Royal Society: Interface

http://rsif.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/11/101/20140873

16 – ‘Depression and Anxiety Disorders Damage Your Brain, Especially When Untreated’ David Hellerstein, (Website Article), Psychology Today, accessed Dec. 28, 2015

https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/heal-your-brain/201107/depression-and-anxiety-disorders-damage-your-brain-especially-when

17 – ‘Psychedelics and Mental Health: A Population Study’ Teri S. Krebs, (Article In Digital Journal), 2013, PLOS One

http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0063972

18 – ‘Mystical-type experiences occasioned by psilocybin mediate the attribution of personal meaning and spiritual significance 14 months later’ Roland Griffiths et al., (Article in Journal), 2008, Journal of Psychopharmacology [Volume xxx, Issue xx) (2008) pp 1–12]

http://www.maps.org/images/pdf/2008_griffiths_23042_1.pdf

Article originally appeared here: http://www.jameswjesso.com/treating-depression-ketamine/